Flight From Paris To Brussels

March 19 1815

When news came of Napoleon’s escape from Elba and his triumphant march up towards Paris, there was commotion in many households including the d’Arblay’s. M. d’Arblay rushed home from the Tuileries to tell Fanny that Napoleon’s troops could be seen encamped just outside the city gates. Fanny watched from the window as her husband mounted his warhorse, laden with all the paraphernalia of warfare (helmet, bayonet, pistols, ammunition). “Vive le Roi” he shouted as he rode out of the courtyard. He was a member of Louis XVIII’s Garde du Corps. Except for this personal bodyguard, the army deserted the King and went over to Napoleon. Louis made secret plans to flee from Paris to Lille.

Fanny’s most evocative description was

“I ran to the window of a small anteroom, which looked upon the inward court yard. There, indeed, behold him I did – but Oh with what anguish! Just mounting his War Horse – a noble Animal,…it seemed loaded with pistols and equip’d completely for immediate service on the field of Battle – while Deprez, the Groom, prepared to mount another, & our cabriolet was filled with Baggage, & implements of War …he was thus armed and encircled with Instruments of Death – Bayonets, Lances, Pistols, Guns, Sabres, Daggers – oh! Gracious God!…I could not refrain from hastening to have yet another glance, from the Drawing room window, as, followed by his Groom and his cabriolet, he came from under the port Cochere into la Rue de Miromenil. What an impression did that last glance leave upon my spirits. In his Helmet (a grandiose brass helmet of Graeco-Roman design, topped by a large plume) for which his military Cap had lately been altered, by a recent order of the Duc de Berry for all the Body Guards, I had not before seen him.”

It was agreed with Mme d’Hénin that Fanny would go with her to Brussels. There was general indecision and confusion but when M. de Lally sent a message that Bonaparte was within a few hours march of Paris, panic intensified. Mme dHénin ordered horses for the Berlin (an old fashioned, four wheeled covered carriage with a seat behind covered with a hood) but no horses were available, the government having requisitioned them all. Eventually Mme d’Hénin was able to borrow some from a friend to take them for the first stage.

“We now rushed into the carriage, averse, yet eager, between ten and eleven o’clock at night.

As Madame d’Hénin had a passport for herself, we resolved to keep mine in reserve, in case of accidents or separation, and only to produce hers while I should be included in its privileges.

The decision for our route was for Brussels ; the femme de chambre of Madame d’Hénin within, and the valet, Le Roy, outside the carriage, alone accompanied us, with two postilions for the four horses.

General d’Arblay with his horse by Carle and Horace Vernet

Le Bourget

“We arrived at Le Bourget, a long straggling town. Here we were meant to stop and change horses. But all was still, and dark, and shut up. It was the dead of the night, and no sort of appearance or effect of alarm seemed to disturb the inhabitants of the place…finally were more successful, though even then we could obtain only a single apartment, with 3 beds…The Town, probably, was filled with fellow flyers from Paris.”

Of course, Fanny was concerned about her husband in the King’s bodyguard but M. de Lally’s son-in-law and Mme d’Hénin’s nephew were both in danger in the King’s regiments. Mme d’Hénin’s servant Le Roy was sent back to Paris to find out if the King had in fact left Paris. He returned at 6 am with the news that the King and his Guards and family had all left Paris “but whither had not transpired.”

“No longer easy to be so near Paris, we hastily prepared to get on for Brussels… M. de Lally now accompanied us, followed by his Valet in a Cabriolet.”

Senlis

“The road, the fields, the Hamlets, all appeared deserted. Desolate and lone was the universal air. I have since concluded that the people of these parts had separated into two divisions; one of which had hastily escaped, to save their lives and loyalty; while the other had hurried to the Capital to greet the conqueror: for this was Sunday, the 20th of March.

What were my sensations on passing through Senlis, so lately fixed for my three months abode with my General, during his being in service. When we stopped at a nearly empty inn, during the change of horses, I enquired after Madame Le Quint, and some other ladies who had been prepared to kindly receive me — but they were all gone ! hastily they had quitted the town, which, like its environs, had an air of being generally abandoned. The desire of obtaining intelligence made Madame d’Hénin most unwilling to continue a straight forward journey, that must separate her more and more from the scene of action.”

Chateau de Mouchy

“We wandered about, however, I hardly knew where, save that we stopped from time to time at small hovels in which resided tenants of the Prince or of the Princess de Poix, who received Madame d’Hénin with as much devotion of attachment as they could have done in the fullest splendour of her power to reward their kindness…”

(Prince and Princess de Poix were close friends of Mme, d’Hénin who had often stayed at the Chateau.)

Roy

“We touched, as I think, at Noailles, at St. Just, at Mouchy, and at Poix — but I am only sure we finished the day by arriving at Roy, where still the news of that day was unknown. What made it travel so slowly I cannot tell; but from utter dearth of all the intelligence by which we meant to be guided, we remained, languidly and helplessly, at Roy till the middle of the following Tuesday, 21st March.

About that time, some military entered the town, & our Inn. We durst not ask a single question, in our uncertainty to which side they belonged, but the 4 Horses were hastily ordered…”

Philippe-Louis-Marc-Antoine, comte de Noailles, prince-duc de Poix, and 2nd Spanish and 1st French duc de Mouchy (21 November or 21 December 1752 – 17 February 1819), was a French soldier, and politician of the Revolution.

Amiens

“But Brussels was no longer the indisputable spot, as the servants overheard some words that implied a belief that Louis XVIII was quitting France to return to his old asylum, England. It was determined, therefore, though not till after a tumultuous debate between La Princesse and M. de Lally, to go straight to Amiens, where the Prefect, M. Lameth, was a former friend, if not connexion by alliance of the Princess.”

(Her nephew, M. de la Tour du Pin had been the Prefect in Amiens when Louis XVIII stayed there on his return to France in April 1814 after being restored to the throne of France by the Armies of the Sixth Coalition.)

“We had now to travel by a cross road, & a very bad one, & it was not till night we arrived at the suburbs.

The officers of the Police who demanded our passports were evidently at a loss whether to regard them as valid or not…they desired us, as it was so late & dark, to find ourselves a lodging in the suburbs, & not enter the City of Amiens till the next morning. Again followed a tumultuous debate, which ended in the hazardous resolve of appealing to the Prefect…This appeal ended all Inquisition. We were treated with deference …An order to the police officers to let us enter the City and be conducted to an Hotel named by M. Lameth. My passport being held back, I only made one of the family of la Princesse.

We had an immensely long drive through the city of Amiens where we came to the indicated hotel. But here Madame d’Hénin found a note that was delivered to her by the Secretary of the Prefecture, announcing the intention of the prefect to have the honour of waiting upon her. When M. Lameth was announced, M. de Lally and I retired to our several chambers. At length I also was summoned.

Madame d’Hénin came out to me upon the landing- place, hastily and confusedly, to say that the prefect did not judge proper to receive her at the prefecture, but that he would stay and sup with her, and that I was to pass for her femme de chambre, as it would not be prudent to give in my name, though it had been, made known to M. Lameth. But the wife of an officer so immediately in the service of the King must not be specified as the host of a prefect, if that prefect meant to yield to the tide of a new government. I made, however, no enquiry.

Princesse d’Hénin’s Title

I was afterwards informed that news had just reached him, but not officially, that Bonaparte had returned to Paris. Having heard, therefore, nothing from the new government, he was able to act as if there were none such, and he kindly obliged Madame d’Hénin by giving her new passports, which, should the conquest be confirmed, would be safer than passports from the ministers of Louis XVIII. at Paris. I was here merely included in her family, and he advised that my name should be concealed. There was peculiarly less danger for Madame d’Hénin, to whom Talleyrand, while he held the seals of Bonaparte, had accorded the preservation of her title, as being hers from a Prince of the Low Countries, or La Belgique, and therefore not necessarily included in the revolutionary sacrifice of rank. Her claim, therefore, to the honours of her name having, of course, never been disputed on the King’s side, and having been ratified on that of Bonaparte while in power made her now one of the persons least liable to involve any magistrate in difficulty for being allowed to pass through his domain, whatever might be the issue of the present public conflict.

Our design of following the King, whom we imagined gaining the sea-coast to embark for England, was rendered abortive from the number of contradictory accounts which had reached M. Lameth as to the route he had taken. Brussels, therefore, became again our point of desire: but M. Lameth counselled us to proceed for the moment to Arras, where M. (I forget his name) would aid us either to proceed, or to change; according to circumstances, our destination in an instant.”

To Arras 11pm

“No time, however, was to be lost, lest M. Lameth should be forced himself to detain us. Horses, therefore, he ordered for us, and a guide across the country for Arras”.

It was now about 11 at night. The road was of the roughest sort, and we were jerked up and down the ruts so as with difficulty to keep our seats. It was also very dark, and the drivers could not help frequently going out of their way, though the guide, groping on, upon such occasions, on foot, soon set them right. It was every way a frightful night.

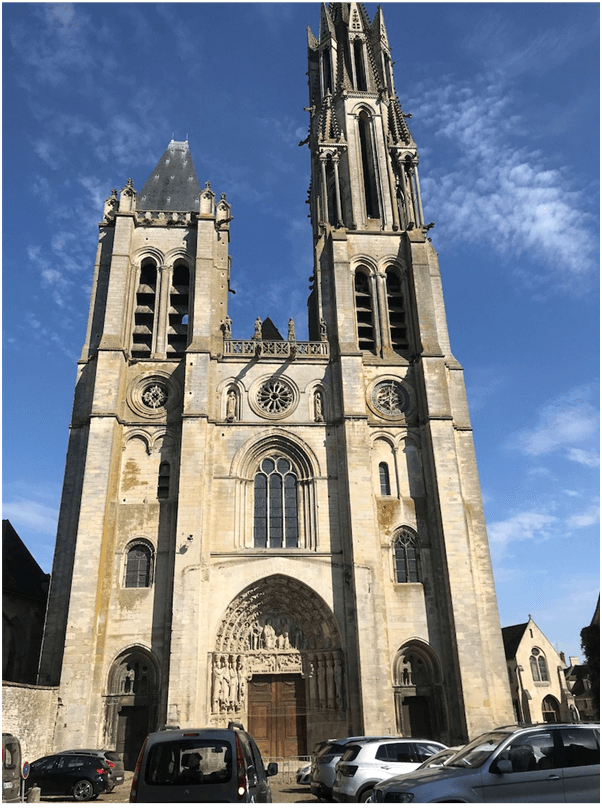

At what hour we arrived at Arras on Wednesday, the 22nd March, I cannot tell ; but we drove straight to the Prefecture, a very considerable mansion (formally the episcopal palace rebuilt in 1780. Pillaged and sold during Revolution but later restored), surrounded with spacious grounds and gardens, which to me, nevertheless, had a bleak, flat, and desolate air, though the sun was brightly shining. Madame sent in the Note from M Lameth. The answer was a most courteous invitation of entrance…

Meanwhile, an elegant Breakfast was prepared for a large company…This repast had a cheerfulness that, to me, an English woman, was unaccountable…The King had been compelled to fly his Capital; no one knew whether he meant to resign his Crown…or whether to contest it in sanguine civil War.

While preparing for this ceremony, the Commander again returned, and said he had positive information that the defection was spreading, and that whole troops and companies were either sturdily waiting in inaction, or boldly marching on to meet the Conqueror.

Our table was now broken up, and we were wishing to depart, ere official intimation from the Capital might arrest our further progress. Both our horses were still too tired, and no other were to be procured. We became very uneasy, and uneasiness began to steal upon all around us.

At length however, about noon, we set off, accompanied by the Prefect and all his family, to our Carriage.”

Douay

“At Douay, we had the satisfaction to see still stronger outward marks of attachment to the King and his cause, for in every street through which we passed, the windows were decked with emblems of faithfulness to the Bourbon dynasty, white flags, or ribands, or handkerchiefs. All, however, without commotion, all was a simple manifestation of respect. No insurrection was checked, for none had been excited; no mob was dispersed, for scarcely any one seemed to venture from his house. – “

Orchies

“Our intention was to quit the French territory that night, and sleep in more security at Tournay; but the roads became so bad, and our horses grew so tired, that it was already dark before we reached Orchies. M. de Lally went on from Douy in his cabriolet, to lighten our weight, as Madame d’Hénin had a good deal of baggage. We were less at our ease, in thus perforce travelling slower, to find the roads, as we proceeded from Douay, become more peopled. Hitherto they had seemed nearly a blank. We now began, also, to be met or to be overtaken, by small parties of troops”.

At Orchies, where we arrived rather late in the evening, we first found decided marks of a revolutionary state of things. No orders were sent by either party. The King and his government were too eminently in personal danger to assert their rights, or retain their authority for directing the provinces; Bonaparte and his followers and supporters were too much engrossed by taking possession of the capital, and too uncertain of their success, to try a power which had as yet no basis, or risk a disobedience which they had no means to resent. The people, as far as we could see or learn, seemed passively waiting the event ; and the constituted authorities appeared to be self-suspended firm their functions till the droit du plus fort should ascertain who were their masters.

Nevertheless, while we waited at Orchies for horses, news arrived by straggling parties which, though only whispered, created evidently some disturbance ; a sort of wondering expectation soon stared from face to face, asking about the eye what no one durst pronounce by the voice; what does all this portend ? and for what ought we to prepare ?

Suburbs & Orchies

It was past eleven o’clock, and the night was dark and damp, ere we could get again into our carriages; but the increasing bustle warned us off, and a nocturnal journey had nothing to appal us equally with the danger of remaining. We eagerly, therefore, set off, but we were still in the suburbs of Orchies, when a call for help struck our ears, and the Berlin stopped. It was so dark, we could not at first discern what was the matter, but we soon found that the carriage of M. de Lally had broken down. Madame d’Hénin darted out of the Berlin with the activity of fifteen. Her maid accompanied her, and I eagerly followed. Neither M. de Lally nor his man had received any injury, but the cabriolet could no longer proceed without being repaired. The groom was sent to discover the nearest blacksmith, who came soon to examine the mischief, and declared that it could not be remedied before daylight. We were forced to submit the vehicle to his decree ; but our distress what to do with ourselves was now very serious. We knew there was no accommodation for us at the inn we had just quitted, but that of passing the night by the kitchen fire, exposed to all the hazards of suspicious observation upon our evident flight. To remain upon the high road stationary in our Berlin might, at such a momentous period, encompass us with dangers yet more serious.

We were yet unresolved, when a light from the windows of a small house attracted our attention and a door was opened at which a gentlewoman some- what more than elderly stood, with a candle in her hand, that lighted up a face full of benevolence, in which was painted strong compassion on the view of our palpable distress. Her countenance encouraged us to approach her, and the smile with which she saw us- come forward soon accelerated our advance; and when we reached her threshold, she waited neither for solicitation nor representation, but let us into her small dwelling without a single question, silently, as if fearful herself we might be observed, shutting the street door before she spoke. ‘ She then lamented, as we must needs, she said, be cold and comfortless, that she had no fire, but added that she and her little maid were in bed and asleep, when the disturbance on the road had awakened her, and made her hasten up, to enquire if any one were hurt. We told as much of our story as belonged to our immediate situation, and she then instantly assured us we should be welcome to stay in her house till the cabriolet was repaired.

Without waiting for our thanks, she then gave to each a chair, and fetched great plenty of fuel, with which she made an ample and most reviving fire, in a large stove that was placed in the middle of the room. She had bedding, she said, for two, and begged that, when we were warmed and comforted, we would decide which of us most wanted rest. We durst not, however, risk, at such a moment, either being separated or surprised; we entreated her, therefore, to let us remain together and to retire herself to the repose her humanity had thus broken. But she would not leave us. She brought forth breads butter, and cheese, with wine and some other beverage, and then made us each a large bowl of tea. And when we could no longer partake of her hospitable fare, she fetched us each a pillow, and a double chair to rest our heads and our feet.

Thus cheered and refreshed, we blessed our kind hostess, and fell into something like a slumber, when we were suddenly roused by the sound of trumpets, and warlike instruments, and the trampling of many horses, coming from afar, but approaching with rapidity. We all started up alarmed and presently the group, perceiving, I imagine, through the ill-closed shutters, some light, stopped before the house, and battered the door and the window, demanding admission. We hesitated whether to remain or endeavour to conceal ourselves; but our admirable hostess bid us be still, while, calm herself, she opened the street door, where she parleyed with the party, cheerfully and without any appearance of fear, and telling them she had no room for their accommodation, because she had given up even her own bed to some relations who were travelling, she gained from them an applauding houza and their departure.

She then informed us they were Polish Lancers, and that she believed they were advancing to scour the country in favour of Bonaparte. She expressed herself an open and ardent loyalist for the Bourbon, but said she had no safety except in submitting, like all around her, to the stronger powers. Again, by her persuasion, we sought to compose ourselves; but a second party soon startled us from our purpose, and from that time we made no similar attempt. I felt horrified at every blast of the trumpet, and the fear of being made prisoner, or pillaged, assailed me unremittingly.

At about 5am our carriages were at the door. We blessed our benevolent hostess, took her name and address, that we might seek some means of manifesting our gratitude, and then quitted Orchies.”

Fanny summarised it in a letter to her son saying that

at Orchies, the last frontière town of France, the wheel of the carriage broke at 11 at night, every inn was full, the wheel could not be mended under 4 or 5 hours and it rained continually. Then they were rescued by a good woman who heard their cries of distress.

To the frontier

“For the rest of our journey till we reached the frontiers, we were annoyed with incessant small military groups or horsemen ; but though suspiciously regarded, we were not stopped. The fact is, the new government was not yet, in these parts, sufficiently organised to have been able to keep if they had been strong enough to detain us. But we had much difficulty to have our passports honoured for passing the frontiers; and if they had not been so recently renewed at Amiens I think it most probable our progress would have been unimpeded till new orders and officers were entitled to make us halt. “

Tournay

Chez Thibaut, Hotel de l’Imperatrice, à Tournay – près Lille – dans la Belgique (in the rue des Meaux off Tournai’s Grand’ Place)

“Great, therefore, was our satisfaction when, through all these difficulties, we entered Tournay — where, being no longer in the lately restored kingdom of France, we considered ourselves to be escaped from the dominion of Bonaparte, and where we determined therefore to remain till we could guide our further proceedings by tidings of the plan and the position of Louis XVIII. We went to the most considerable inn (Hôtel d’Impératrice), and all retired to sleep which, after so much fatigue, mental and bodily we required, and happily obtained. The next day we had the melancholy satisfaction of hearing that Louis XVIII also had safely passed the frontiers of his lost kingdom.”

A few months earlier Mme de la Tour du Pin and her husband were travelling from Brussels to Paris and stopped over in Tournai

“We paid long visits not only to the Cathedral, but also to two factories, one producing fine carpets and the other porcelain. We saw the magnificent chalice of St Eleuthera, which had been dug up not long before in a garden where it must have lain hidden since the days of the very first Frankish invasion.”

Atot (ATH)

“I have very little remembrance of my journey, save of the general cleanliness of the Inns and the people on our way, and of the extraordinary excellence, sweetness, lightness, and flavour of the bread, in all its forms of loaves, rusks, cakes, rolls, tops and bottoms. I have never tasted such elsewhere. At the town at which we stopped to dine which I think was Atot, we again met M. et Madame de Chateaubriand.

This was a mutual satisfaction and we agreed to have our meal in common. I now had more leisure, not of time alone, but of faculty, for doing justice to M. de Chateaubriand, whom I found amiable, unassuming, and, though somewhat spoilt by the flattery to which he had been accustomed, whilst free from airs or impertinent self-conceit… Madame de Chateaubriand also gained ground by this acquaintance. She was faded, but not passée, and was still handsome, and well as highly mannered, and of a most graceful carriage.

We separated from this interesting pair with regret, and the rest of our journey to Brussels was without event, for, to passport difficulties we became accustomed, and grew both adroit and courageous in surmounting them.”

Brussels

320 Rue de la Montagne, 26 March 1815

“Arrived at Brussels, we drove immediately to the house in which dwelt Madame la Comtesse de Maurville. That excellent person had lived many years in England, an emigrant, and there earned a scanty maintenance by keeping a French school. She had now retired upon a very moderate pension, but was surrounded by intimate friends, who only suffered her to lodge at her own home. She received us in great dismay, fearing to lose her little all by these changes of government. I was quite ill on my arrival; excessive fatigue, affright, and watchfulness overwhelmed me. I kept my bed a day or two ; but with the aid of Dr. James’s medicines, and my own earnest efforts to employ every faculty as well as every moment in researches, I then recovered and again went to work.”

My trip following the flight from Paris to Brussels

Maryly and I decided that our first stop would be Senlis. Le Bourget is only about 10.6 kms from central Paris and has two major motorways going through it as well as the airport.

Senlis

We had booked in to Chambres d’hotes Parseval and arranged with our hosts that we would arrive about 5 pm (we subsequently learned the timing was to fit in with their golf match). It was a lovely old house and would have been there when Fanny passed through. We had time to visit the town keeping an eye out for a restaurant. It was charming with many cobbled pedestrian only streets. It had become the Royal City of Senlis in the time of the Franks in 981 AD until the reign of Charles X in 1824-1830 and was a base for the King’s army during the 100 days when Louis XVIII reigned. This was why M. d’Arblay had been based there and why Fanny had planned to stay there for three months. We looked at the famous cathedral and went into the gardens of the Palace. On this warm, Sunday afternoon there were many people wandering the streets or drinking and eating in outside cafes. It was such a lovely town, I thought it would indeed be a good place to spend a few weeks.

Chambre d’Hotes Parseval

Oldest corner of the building of Parseval built in 17th century

View from my bedroom window at Chambre d’Hotes Parseval

Park of the Royal Palace with vestiges of the Royal Palace

Senlis on a Sunday

Streets of Senlis

Notre-Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame cathedral (12th-16th centuries)

Senlis

Royal Palace

Chateau de Mouchy

It was 21 miles from Senlis to the Chateau de Mouchy. By setting the Satnav (Irma) it was not stressful. We could admire the countryside – woods on either side of the first road, the D1330 to Creil past the Parc Technologie Atlanta modern building, then flat country on to N16 to Vaux, then slightly hilly on the D137 Cauffrey to Mouy.

We stopped at Mouy village to check our bearings. Then on to Chateau de Mouchy. We were struck by the beauty of the roses climbing the walls of the immaculately preserved buildings. Then, finding a small green where we could park, opposite a terrace of restored houses with lovely front gardens, we pulled in and got out. We were looking around when a car came out of the terrace driven by a man who was clearly wondering what we were up to. He stopped, and noticing the English number plates on the car, spoke to us in perfect English.

We explained that we were on a Fanny Burney tour and that she had mentioned Mouchy in her diary because she was travelling with Princess d’Hénin who was a close friend of the Prince and Princesse of Poix (also of Noailles and Mouchy) and had frequently stayed with them at the Chateau. This charming man then announced that he was himself the Prince of Poix, the 13th as the title had now passed to his eldest son. What an incredible coincidence; we were elated. He told us that the chateau had 200 main rooms and 23 staircases and had been pulled down by his father who had built a modern chateau. The eldest son of “our” Prince now lived there with his wife and children – “both daughters” said our Prince, so he has urged his son to “keep on trying” .

Other members of the family lived in various houses on the estate either recently built or renovated. We were allowed to go through the locked gates into the grounds of the chateau but warned not to go too close to the building because it was heavily alarmed. He told us that during the Terror in 1793, the guards from Beauvais were sent to bring Prince and Princesse de Poix to Paris to be guillotined. But as they were respected by the local people who considered the Prince a good, kind landlord, the people of Mouchy wouldn’t let them be taken. But Robespierre wasn’t going to be deterred and he sent guards from Paris to get them and they were both beheaded. In World War II, the Germans occupied the chateau. They were working on the V2 in Beauvais from where they were launched, but the men lived at Mouchy. They did a lot of damage and when they left they tried to burn it down. The family had put a lot of paintings and objects d’art into museums for safe keeping but the Germans stole any that were left.

We had to press on as we were scheduled to get to Tournai in Belgium. We passed through the places Fanny mentioned – Noailles, St. Just en chausée where we were impressed by the wind farms. Roye where Fanny’s party were forced to spend several days, there seemed to be almost nothing except one store.

Then on the D916 from St. Just to Esquennoy where we stopped to look at a wonderful church (Église Saint Pierre).

Chateau de Mouchy

13th Prince of Poix - Antoine Georges Marie de Noailles, 9th Duke of Mouchy and Duke of Poix

Maryly at Mouchy le Chatel

Village house in Mouchy le Chatel

In the grounds of the Chateau de Mouchy

All there was of Roye

Église Saint Pierre at Essquenoy

Amiens

On the D1001 Route Nationale rather than the motorway A16. It took 20 minutes to get through the suburbs along Avenue du 14 Juillet 1789 with 20th century houses, supermarkets off to the side and then a long straight road descending into the city centre but it was narrow with cars parked on one side of the single lane road finally reaching the Place Leon Goutier. Many references to Jules Verne who lived there, and to Emmanuel Macron who was born there. We crossed over the Somme with all the resonance that name conjures up.

Getting through the suburbs however took 15 minutes along busy roads with a lot of new buildings, factories, houses all very neat and tidy looking. The town was fought over during both World Wars, suffering significant damage. After the Second World War the city was rebuilt according to Pierre Dufau’s plans with wider streets. The newer structures were primarily built of brick, concrete and white stone with slate roofs.

Arras

We decided to take the fastest route to Arras, on the A1 motorway (not the roughest sort of road, as Fanny’s party had to endure at 11pm). We left the suburbs at 4.15 with an estimated time of 1 hour to Arras. Those of us who have driven on the A26 from Calais are very familiar with the name of Arras at the junction with the A1 to Paris.

Arras was, like Amiens badly bombed and occupied by Germans during both World Wars so there are many new buildings and whole new suburbs. It was so badly damaged by 1918 that three quarters had to be rebuilt. It is now a World Heritage site.

Douai

We came out of Arras on the D917 and on to the D950. Douai is still in France and suffered in both World Wars. We could see a new Planetarium being built – Planetarium & observatory of Douaisis which links with Arkeos, the archaeological Museum and park. On the D938 to Orchies we go through Flines lez Raches and Coutische. It all seems like one long, straggling street with some old houses being infilled by new ones in brick and small shops.

The Peace of Amiens after which Fanny was able to return to France – it lasted only one year until May 1803

Hotel de Ville Amiens

Amiens

Amiens

L’église St. Nicolas en Cité, Arras

Hotel de la Prefecture - Where Fanny and her party were entertained – rebuilt in 1856

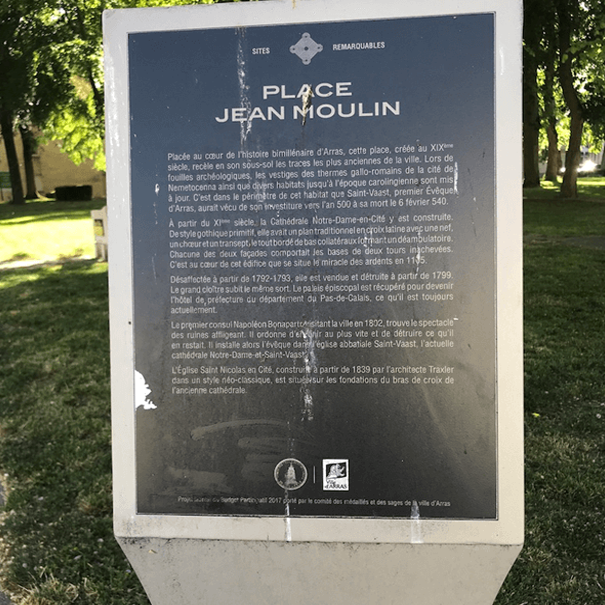

Place Jean Moulin Arras

Place Jean Moulin Arras

Place Jean Moulin Arras

Council offices Pas de Calais, Arras

Modern architecture, Arras

Orchies

Fanny refers to the suburbs of Orchies and being rescued by a kind elderly couple. The ribbon development continued for many miles out of Orchies so it was impossible to get any idea of what it would have been like in 1815. It was pretty depressing in 2022.

Tournai

Across the border and into Belgium. Not the great sense of relief that Fanny and her companions felt. The only noticeable change was that names were in two languages. We stayed a few miles out of Tournai in a lovely rural hotel called Ferme Delgueule. Next morning we went into Tournai and found Hotel de l’Imperatrice which was now a restaurant; one of many which border the main square (Grand Place). We searched for coffee, it being 11 am and walked through the many tables which were out in the square with people sitting at them not with coffee but with beer – after all this was the home of Belgium beer. We found one place happy to provide coffee but when it came it was buried in whipped cream.

We wandered on but the whole town seemed empty except for the tourists in the main square. We found the cathedral which was vast with scaffolding over many parts. It is now a Heritage site as more than Eleuthera has been dug up. There are excavations revealed and glass covered all along one side. There was no sign of carpets or porcelain whose makers Mme de la Tour du Pin visited but there were plenty of chocolate shops and factories and car showrooms lined the roads around the town.

Ath

Like Fanny I have little remembrance of Ath as we were keen to get to Brussels. It is known as the Cité des Géants after the Ducasse d’Ath festivities which take place every year on the fourth weekend in August. Huge figures representing Goliath, Samson, and other allegoric figures are paraded through the streets, and Goliath’s wedding and his famous fight with David are re-enacted (according to Wikipedia).

Next stop Brussels. It took Fanny and her party 7 days to get from Paris to Brussels which today by car would take three and a half hours. Maryly and I spent 2 days on that part of the trip.

Douai

Orchies

Orchies

Street in centre of Orchies

Suburbs of Orchies

Tournai rue des Meaux off Grand’Place

Grand Place Tournai

Rue de la Wallone Tournai

Notre- Dame Cathedral Tournai

Film crew working in Notre-Dame cathedral – Ukrainian flag displayed

Excavations in the cathedral