Fanny Burney’s Family

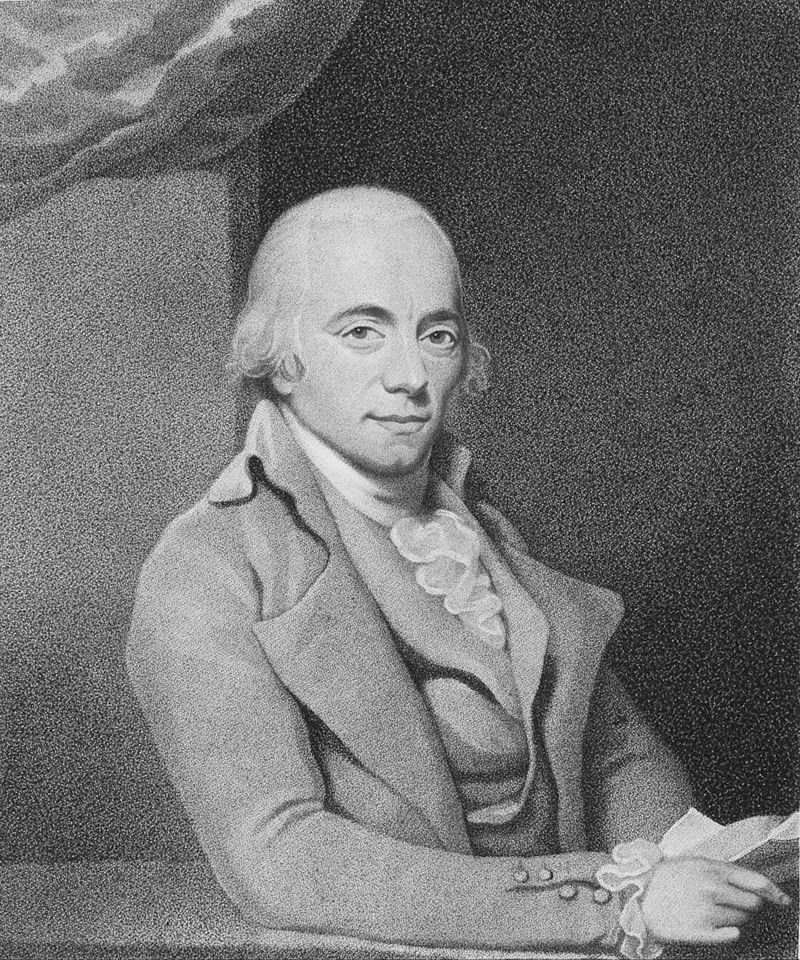

Dr Charles Burney

1726-1814

Fanny’s father was a remarkable man, very hard working, a talented musician and writer, described in an article full of anecdotes in The Musical Times in 1904 as having “dogged perseverance and unabated enthusiasm for work which characterized him throughout his long life”. There was special talent in music and art as well as brains in the family. Added to this, Charles had charm and manners. He was greatly loved and admired by his many friends. Dr Johnson said “there was not in the world such another man for mind, intelligence and manners such as Dr. Burney”.

Born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Charles, his parents and 9 siblings moved further north on the Welsh border to Chester, the major port for passengers going to Ireland. In 1741 Handel visited the city on his way to Dublin for the first performance of The Messiah. Young Charles took part in a rehearsal of parts of the Messiah and repeated an anecdote about a bass singer who displeased Handel who rounded on the singer, Janson, “swearing in five languages cried out in broken English ‘You schauntrel! Tit not you dell me dat you could sing at soite?’ – ‘Yes, sire’ replied Janson, ‘and so I can, but not at first sight'”.

Another and ultimately more important passer – through Chester on his way back to London from Dublin, was the distinguished composer of Rule Britannia, Dr. Arne. Charles who was then 18, played the organ in the cathedral and came to the attention of Dr. Arne who offered to take him as a pupil for three years. So Charles came to London to study composition and to play the harpsichord, the organ, and fiddle in Dr. Arne’s orchestra at Drury Lane, sometimes under the baton of Handel.

Charles wrote: “In 1745 I performed in Handel’s band, sometimes on the violin and sometimes on the tenor and by attending the rehearsals, generally at his own house in Lower Brook Street and sometimes at Carlton House (residence of Prince of Wales) I gratified my eager curiosity in seeing and examining the person and manners of so extraordinary a man, as well as hearing him perform on the organ. He was a blunt and peremptory disciplinarian on these occasions, but had a humour and wit in delivering his instructions, and even in chiding and finding fault, that was peculiar to himnself, and extremely diverting to all but those on whom his lash was laid.” Charles played in the London premieres of two Handel oratorios “Hercules” and Belshazzar”.

Charles became acquainted with a young man, Fulke Greville “the finest gentleman about town” Fanny said in later years, who persuaded Charles to give up his apprenticeship and become his tutor in music and art. Charles was thrown into a dissipated set of young aristocrats and wealthy men. However, it fairly soon came to an end as Fulke now married, planned an extensive tour of Europe with his wife and Charles found that he could not go with them as he wished to marry. This he did in June 1749 and in October he took a job as organist of St. Dionis Backchurch, a Wren church in Fenchurch Street (now demolished and replaced by tall modern buildings)

Esther Sleepe Burney

1725-1762

At a dance given at the house in Hatton Garden of his elder brother, a dancing master, Charles met and fell in love with a Miss Esther Sleepe. What a very special person she was. Little of her was said by Fanny except that she was much loved, that she read Shakespeare, Pope and Dryden to her children. I had imagined that she was totally occupied in bearing and rearing children. She had 9 children in 11 years, 6 of whom survived. However, in a fascinating article by Amy Louise Erickson (Esther Sleepe, Fan Maker, and Her Family; Duke University Press) she reveals that this was a deliberate cover-up by the Burneys to hide the family association with trade. For Esther, her sisters and her mother were all successful fan makers with shops in Cheapside which was the most exclusive shopping street in the City. Esther’s was at the east end “opposite the Old Jewry in the Poultry”. After her marriage, she moved her shop to Fenchurch Street (near the church where Charles was an organist) continuing to sell fans and jewellery, wholesale and retail.

I was intrigued to see in the recent television historical drama series, BELGRAVIA, set in early 19th century, that when the office of the young man Charles Pope was shown it was 521 Bishopsgate, and one of the signs on the elegant building was for a fan maker.

Esther had a child in May 1749 and she married Charles on 25 June 1749. They were 23 and 24. According to Amy Louise Erickson, Esther Burney, not Charles, was the primary earner in the household.

This sentence in the Cambridge Companion to Frances Burney furnishes the only information that has, to date, been definitively known:

“[Frances’s] much beloved mother had died shortly after the birth of Charlotte, leaving Charles with six children, the eldest of whom was only thirteen and the youngest just six months.”

James Gillray (1756–1815), "A little music - or - the delights of harmony". National portrait Gallery.

Esther Hetty Burney

1749-1832

Esther, the eldest daughter, was blessed with beauty, good sense, good humour, plus a love of fun. She was besides remarkably musical, and according to the Gentleman’s Magazine, “was won’t to astonish her father’s guests, at a very early age, by her skilful instrumentalism”. Certainly at 8 she was playing in public as a harpsichordist and performed at the little Theatre in the Haymarket on April 23 1760. HRH the Duke of York so admired her performance of Scarlatti sonatas, that he asked Dr Burney to turn them into concertos for her to play. She married a cousin Charles Rousseau Burney, also a fine musician and they arranged and performed at musical concerts in family houses in London for distinguished guests. In a letter Fanny wrote to Samuel “Daddy” Crisp in May 1775 she starts “Our concert proved to be very much the thing” and went on to describe all the distinguished, titled guests and the musical performances until she came to “the great Gun of the Concert, namely a Harpsichord Duet between Mr Burney (Hetty’s husband) and my sister. It is the Noblest Composition that was ever made. They came off with flying Colours – Nothing could exceed the general applause. Mr Harris was in extacy; Sir James Lake who is silent and shy, broke forth into the warmest expressions of delight…the charming Baroness repeatedly declared she had never been at so agreeable a Concert before…” A few months later there was another concert for Prince Orloff of Russia where husband and wife performed The Grand Duet of Muthel once again to rapturous applause and jokes about the “harmony” of husband and wife.

From Susanna Burney’s Journal in about 1766 when she returned from Paris, she describes her two older sisters –“The characteristics of Hetty seem to be wit, generosity, and openness of heart:—Fanny’s,—sense, sensibility, and bashfulness, and even a degree of prudery. Her understanding is superior, but her diffidence gives her a bashfulness before company with whom she is not intimate, which is a disadvantage to her. My eldest sister shines in conversation, because, though very modest, she is totally free from any mauvaise honte: were Fanny equally so, I am persuaded she would shine no less. I am afraid that my eldest sister is too communicative, and that my sister Fanny is too reserved. They are both charming girls.”

James (Jem) Burney

1750-1821

At the age of ten, James entered the Navy under Admiral Montagu as a nominal midshipman, thanks to an introduction from his father who had dined with the Admiral. James was considered to be unusually bright and manly and full of vivacity and high spirits. In her Journal on December 20 1769, Fanny makes a rather gushing assessment of his character:

“My dear brother has now been home these three weeks!…James’s character appears the same as ever – honest, generous, sensible, unpolished; always unwilling to take offence, yet always eager to resent it; very careless, and possessed of an uncommon share of good nature; full of humour, mirth and jollity; ever delighted at mirth in others, and happy in a peculiar talent of propagating it himself. His heart is full of love and affection for us – I sincerely believe he would perform the most difficult task which could possibly be imposed on him, to do us service…”

He rose to the rank of rear-admiral. He sailed twice round the world with Captain Cook as far north as Siberia and as far south as the Antarctic circle and was with Captain Cook at his death. On these travels, he observed and recorded material on the places and cultures, learning the local languages and transcribing local music. After his retirement from illness in 1784, he took up writing, using the Journals he had kept on his voyages. He edited an edition of William Bligh’s A Voyage to the South Sea in HMS Bounty, published in 1792. His major work was A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean, published in five volumes from 1803 to 1817. In 1809, he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

He was a great whist player. Charles Lamb loved him; Southey depicts him as “smoking after supper, and letting out puffs at one corner of his mouth, and puns at the other”.

Susanna Elizabeth

1755-1800

Susanna Elisabeth (sometimes referred to as Susette), named after Charles’s twin sister, “was also remarkable for her sweetness and charm”. Joseph Baretti praised her dolcissima voce; her knowledge of music was exact and critical. She was a regular fixture in her father’s London music salon, and she mixed with many famous musicians. Her letters provide unique insight into London’s musical culture of the eighteenth century, as she had privileged access to private events such as rehearsals and informal gatherings. For music historians, Susanna’s notes help to document the network among patrons and artists as well as amateur and professional musicians.

She married Captain Molesworth Phillips (1755-1832) in October 1780. Phillips was an officer in the Royal Marines, and a close friend of her brother James. He was also on Captain Cook’s last expedition when he apparently behaved with great bravery. However, he was not a good husband which distressed the Burney family, in particular Fanny to whom Susanna was very close.

Fanny Burney

1752 – 1840

Fanny Burney (1752 -1840) was a writer of novels, diaries and letters. She lived in England and France at very turbulent times and she kept a daily record of what was going on.

She published her first novel anonymously when she was 26 but when it became known that she was the author, she was taken up by the literary elite of London.

She married a Frenchman, Alexander d’Arblay, and lived with him in Paris for 10 years and even followed him to Waterloo where the battle was being fought against Napoleon.

Artist: Paul Sandby, British (1731–1809)

Title: Group portrait of Fanny Burney, Susan Burney, Richard Burney and Mr. Samuel Crisp

Charlotte Anne

1761-1838

She was also a writer. She married, firstly, the physician Clement Francis (c. 1744–1792) and, secondly, the stockjobber, pamphleteer and poet Ralph Broome (1742–1805). She was her father’s “librarian” and was a loss to him when she married as he depended on her to sort all his writings, music and materials.

In 1818 Broome asked Southey for a poem commemorating her younger son Ralph Broome (1801–1817). The Poet Laureate normally disliked writing to order, but felt that this was a request he could not refuse. He produced an epitaph (‘Time and the World, whose magnitude and weight’), sent to Broome in February 1818 and later inscribed on a memorial to Ralph in St Swithun’s Church, Walcot, Bath. In 1829 Broome lost her eldest son, Clement Robert Francis (1792–1829), a Fellow of Caius College, Cambridge. Southey, who had met Francis in the Lake District, produced a second epitaph, ‘Some there will be to whom, as here they read’, for a memorial to him.

Charles Burney

1757-1817

The second of Charles and Esther’s children to be named Charles, an earlier son named Charles had died. At 10 he went to Charterhouse School and on to Cambridge. But he was sent down for stealing books from the library. Later he recovered his reputation and became distinguished as a Greek Scholar. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (1802), made professor of ancient literature at the Royal Academy (1810), and elected to the Literary Club (1810). In 1808 he was ordained as an Anglican priest. He advanced rapidly in the Church of England, becoming rector of the rich living of Cliffe, Kent, and of St. Paul’s, Deptford, as well as serving as a royal chaplain to King George III. After his death his library was acquired by Parliament for £13,500 and deposited in the British Museum. This large,valuable collection of printed books, newspapers and playbills,is now in a special Collection at the British Library.

An interesting story about the name “asteroid” reveals something of the family relationships. It was told in 2013 at the 45th annual convention of the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences. An American astronomer, Clifford Cunningham announced that the term “asteroid” (which means star-like) had been invented by Charles Burney and not by Herschel, the astronomer royal to King George III to whom it had always been attributed. Having seen two letters in the Yale Library, Cunningham traced the story to 1802 when scientists were baffled by the discovery of what they thought were two new planets. Herschel argued they were in fact completely different celestial entities and deserved their own identity.

But Herschel needed a name for these new objects, and quickly for his speech to the Royal Society the following week. So the Sunday before the Royal Society meeting, Herschel appealed to Charles Burney Sr, described by Cunningham as “a poet with whom Herschel was collaborating on an educational poem about the cosmos.” Burney considered the question and that night, by candlelight, penned a letter to his son, Greek expert Charles Burney Jr. The elder Burney suggested the words “asteriskos” or “stellula” to describe the new celestial objects. Charles Burney Jr came back with the term asteroid. These two letters are the ones Cunningham saw at Yale. In 1805 Lord Melbourne was giving a dinner for the Prince of Wales and proposed to His Highness that he should invite Dr Burney to which the Prince responded positively but added that the son should be invited, too saying “it is singular that the father should be the best and almost only good judge of music in the kingdom and his son the best scholar”.

Charles’ Second Wife

Elizabeth Allen (Eliza)

1728-1796

Beautiful and intelligent, she married Charles Burney on 2nd October 1767. She was previously married to her cousin Stephen Allen, a wealthy wine merchant in Lynn and had 3 children. (Stephen, Maria and Elizabeth [Bessie) She was a close friend of Esther Burney. Stephen died in 1763 leaving a fortune of £40,000 but when she married Charles Burney she was no longer an heiress owing to unfortunate investments.

Charles and Elizabeth had 2 children – Richard and Sarah Harriet. It was not an entirely satisfactory marriage. Charles’ children disliked their stepmother. She was unhappy, and in later years, often sick. Her favourite daughter Bessie, eloped at the age of 15 to Ypres, France on 12 October 1777 with an undesirable young man named Meeke. However Bessie Meeke went on to write 26 novels.

Richard Burney,

(1768-1808) known as Bengal Dick, because of his association with India, brought disgrace upon the family by his behaviour, was banished by his father in 1786 and died aged thirty-nine, leaving eight children.

Sarah Harriet Burney

(1772 – 1844) was the author of seven novels. She never married. To the family’s horror, she lived with her half-brother, James for five years until he went back to his wife. She earned a living as a governess and a writer.

Music of the Burney Family

-

George Frederic Handel (1685 – 1757)

-

Handel - Rodelinda

-

Aria played by Charles Burney on the organ

in Chester when assistant organist.

-

Charles Burney: Selected Preludes, Fugues, and Cornet Pieces

-

Charles Burney: Sonatas for Four Hands

-

Johann Gottfried Müthel (1728–1788)

-

Clementi Sonata in Eb major Opus 3 No 2 for 4 hands

-

Mozart Sonata for 4 hands K381 played

-

Haydn and his English Friends - Charles Burney (1726 - 1814) Tell us, O