Paris

Fanny joined her husband in France setting out with son, Alex and the daughter of a friend on April 15 1802. They had to take the cross channel diligence, bumping along uneven roads huddled up with various others. “I cross the sea tomorrow -…with 2 children, & not a soul that knows me, or to whom I am known.” They were a day and a night at sea, two and a half days and nights of non-stop travel from Calais to Paris. They finally arrived into the rue Notre Dame des Victoires on Tuesday April 20. M. d’Arblay had waited 4 hours in the cold for their arrival.

1125 (8) Rue de Miroménil

“He has taken me a little apartment in Rue Miromenil, which, though up two pairs of stairs, is really very pretty, and just new papered and furnished. The view from the window is very pleasant, open to the Country, and airy and healthy. I have a good sized (for me) little neat Drawing room, a small ante-room which we make our Dining Parlour, a tidy Bed Chamber, and a closet within it for Alexander. This, with a kitchen and a bit of a bed-room for my maid, all on the same floor, compose my habitation.”

-Letter to Margaret Planta April 21 1802, their room overlooked the ci-devant Hotel Beauvais just then full of lilacs and flowering shrubs

“We have a very comfortable Apartment, in a very pretty & genteel new street, up 3 pairs of stairs, indeed! But all the more pleasant, once mounted, for its height – as we overlook, by that means, & by a short House opposite, a beautiful Garden of the ce divant Hotel Beauvais, which is full of Lilacs and sweet shrubs, & delightful & airy at once. And at once end of our street we have the Country, open to the village of Monsso (Monceau) which we can walk to in a quarter of an Hour, & of which we scent the air all day long; & at the other end, we have literally only to cross rue Ste Honore to be at once in the Elysian Fields. Our Apartment consists of a salon, extremely well furnished, & of a very good size, …a Bed room about double the size of yours…; a dressing room within it, which serves for Alex, – a dark closet for the maid, & a sort of ante room which separates the whole from a little tiny Kitchen…”

-Fanny describing 1185 Rue de Miromenil (later numbered 8) in a letter to her sister, Esther

On a spring afternoon in 1802 the d’Arblays ambled through the gardens of the Tuileries and along the Champs-Elysées into the rue de Miroménil and Fanny called it “one of the prettiest in Paris”.

On May 12 1802, Napoleon was voted Consul for life by the Senate. This was celebrated by a levée, parades, and a review. M. d’Arblay secured admission to the Tuileries for his wife and the Princesse d’Henin to watch from an ante-chamber and to see the First Consul himself review the troops on the parade-ground.

“Our window was that next to the consular apartment, in which Bonaparte was holding a levée…we had the opportunity to examine every dress and every countenance that passed and repassed. This was highly amusing…where the past history and the present office were known…But what was most prominent in commanding notice, was the array of the aides-de-camp of Bonaparte, which was so almost furiously striking, that all other vestments, even the most gaudy, appeared suddenly under a gloomy cloud when contrasted with its brightness…

“At length the two human hedges were finally formed, the door of the audience chamber was thrown wide open with a commanding crash, and a vivacious officer—sentinel—or I know not what, nimbly descended the three steps into our apartment, and placing himself at the side of the door, with one hand spread as high as possible above his head, and the other extended horizontally, called out in a loud and authoritative voice, ‘Le Premier Consul!’

I had a view so near, though so brief, of his face, as to be very much struck by it. It is of a deeply impressive cast, pale even to sallowness, while not only in the eye, but in every feature – care, thought, melancholy and meditation are strongly marked… The review I shall attempt no description of…It was far more superb than anything I had ever beheld; but while all the pomp and circumstance of war animated others, it only saddened me… Bonaparte, mounting a beautiful and spirited white horse, closely encircled by his glittering aides-de-camp, and accompanied by his generals, rode round the ranks…”

Military review in front of Napoleon's new triumphal arch in the courtyard of the Tuileries Palace(1810) by Hippolyte Bellangé

Paris fashion 1802

When she first arrived in Paris in 1802 M. d’Arblay had hired a femme de chamber

“who is to make me fit to be seen …to metamorphose me from a rustic Hermit into a figure that may appear in this celebrated capital…”

“This won’t do! – That you can never wear! That would make you stared at as a curiosity! – Three petticoats! No one wears more than one! Stays! Everybody has left off even corsets – Shift sleeves? Not a soul now wears even a chemise.”

-Fanny quoting her femme de chambre

In a letter to Margaret Planta at Windsor she recollected that Princess Augusta (daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte)

“diverted herself with the thought of seeing me return in the light Parisienne Drapery so much talked of, & in vogue…”

Monceau

Moved to Monceau for the cleaner atmosphere for son, Alex whose health was poor. Their new rooms were only 15 minutes’ walk from the rue de Miroménil, located up on the hill and beside La folie de Chartres, the large garden formerly belonging to the Duc d’Orléans. Now a public park with lilac walks, a river, small lakes and tea-rooms. Their rooms were at 286 rue Cisalpine which was later renamed Rue Monceau.

Carmontelle (1717-1806), attribué à, Vue de la folie de Chartres, aujourd'hui parc Monceau,

vers 1778 - CC0 Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet-Histoire de Paris

Passy

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, was a quaint cluster of cottages built on a bluff overlooking the Seine, just two miles outside the city, with spectacular views across to the capital.

In 19th century, writers and artists gathered there, because its attractive villas were small, cheap and offered peaceful conditions in which to work. The d’Arblay’s friend César, comte de Latour Maubourg lived there. In October 1802 the small amount of money M. d’A had rescued from his inheritance at Joigny was used to buy a house at 54 RUE BASSE (now rue Raynouard). Fanny described it:

“an up & down, queer, odd little building, which we entered by the roof, & of which we could only furnish the first floor, but which had two or three magnificent views from the sides of the windows, & from a Terrace…built up to our first floor from the garden…from one room a superb view of Paris, just far enough off to be picturesque, nay, magnificent; & from another a sweet prospect from the banks of the Seine, of cultivated Hills, whole villas, & beautiful woods & fields.” The house was unfinished except for 3 rooms when they moved in and they couldn’t afford to finish it.

(Their house long since destroyed. In 1840 Balzac lived in a house nearby which can still be visited.)

1803 12 May – Outbreak of War between France and England. Fanny was unable to return to England as she had hoped. Emigration regulations, a blockage and war on the seas made travel difficult or impossible.

In April 1803, M. d’Arblay was granted a pension of 1,500 livres (£62.10s) annually. And in May he got employment as a rédacteur in the Bureau of the Ministère de l’Intérieur, for 2,500 livres (about £100 a year) setting off for the office each day between 8 and 9 am, and returning past 5pm.

Painting by Grevenbroek – Passy et Chaillot vus de Grenelle 1740

Rue du Faubourg St. Honoré, No.100, rue d’Anjou, No 13 and back again to rue de Miroménil No. 1185.

M. d’Arblay found the long walks between Passy and his office, too strenuous and before the winter of 1806 they moved back to central Paris.

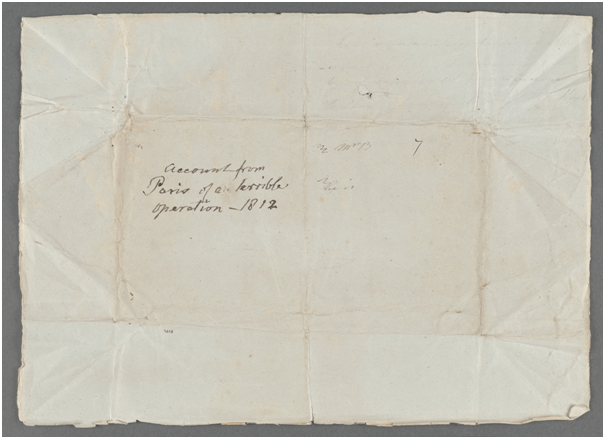

Breast Cancer

1807 letter to Dr. Burney – “Breast attack” treated with a diet of asses’ milk. By summer of 1810 attacks more frequent – spring 1811 pain so severe she was unable to use her right arm (lump in her right breast). Empress Josephine’s obstetrician, M. Dubois saw her and advised rest and avoidance of anxiety but that an operation could be necessary “to avert evil consequences”. The pain was becoming “quicker and more violent, & the hardness of the spot affected encreased”. She no longer had the strength to walk up the three flights of stairs to their rooms, and M. d’A moved her to a first-floor apartment close to their original home on the rue de Miroménil. The surgeon, Baron Larrey confirmed M. Dubois’ view that surgery was necessary.

September 30 1811 – Fanny undergoes mastectomy for breast cancer. The letter she wrote to her sister, Hetty, describing her ordeal is well known. The description is horrifying and still makes me shudder. The whole breast was removed scraped away while she was fully conscious – without any anaesthetic. (This has subsequently been thought to be unnecessary as the tumour was probably not malignant.) She said the operation lasted for seventeen and a half minutes during which she fainted twice. Afterwards she was so weak that her cheeks were drained of all colour and her arms hung lifeless by her side, while she was lifted from the mattress and carried to her bed:

“This removal made me open my Eyes – & I then saw my good Dr Larry, pale nearly as myself, his face streaked with blood, & its expression depicting grief, apprehension, & almost horror”.

She suffered violent spasms during the night but by next morning her fever had gone and by the evening she was taking a little chicken broth. Baron Larrey was first surgeon to Napoleon (later said to have performed 200 amputations in 24 hours at Borodino in September 1812). Her fortitude gained her his respect and friendship and she called on him to help after M.d’Arblay was involved in a near-fatal accident when hit by a horse and cart at Calais in January 1815. She writes: “

We then slowly reached Paris where I had at least the solace to see him under the care of the Prince of Surgeons Dr. Larrey.”

1812 – 14 August - Fanny returns surreptitiously to England with Alexander who is now 17 years old and could be conscripted by Napoleon to fight in Russia. She is also very anxious to see her father who has not been well. They take an American ship that is seized by the English; disembark at Deal.

Letter to Hetty in the British Museum

The Wanderer

1814 – 28 March publishes fourth novel The Wanderer; or, Female Difficulties – dealt with the difficulties that a penniless and unprotected spinster might encounter in earning her living in England. Publishers were eager for the publication. She was offered £3,000 for the contract and at the high price of two guineas each, 3,600 copies of the first edition were sold. But it was not a success. Five volumes in length about a female who without family or fortune had her own way to make in the eighteenth century world; in her search for employment and protection she was driven from one cruel gentlewoman to another, and in a literary style that did not appeal, the reviews were harsh. The sales dropped and she probably received no more than £2,000 in the end. However, for someone interested in the places Fanny Burney visited, it was fascinating how she used her own travelling through the countryside between London and King’s Lynn, Chessington, Tunbridge Wells, Mickleham, Teignmouth, Bath and countless other places and the eighteenth century road comes to life.

It has subsequently been said that “The Wanderer” was not written by Fanny Burney but by Jane Austen’s cousin, Eliza de Feuillide. In the review section of the book on Amazon there is an interesting piece which I will quote although I don’t agree with it.

Book Review of The Wanderer

‘When this book was published originally, it was condemned by critics at the time as complete trash, which it is. Critics of the time said it was totally impossible that the author of the book could be the same as the author of the other Fanny Burney novels.

This was because this was the only one of the novels that was written by Fanny Burney. The other novels were written by Jane Austen’s cousin and sister in law, Eliza de Feuillide. We know that The Wanderer was written by Fanny Burney herself as at the time she was stranded in France and so Eliza could not have written it.

It is probable that Eliza was a harpsichord pupil of Fanny’s father Charles Burney. Fanny was her father’s secretary and so when Eliza was looking for a secretary herself, Fanny would have been the obvious choice. Eliza could not publish the books under her own name because she was the illegitimate daughter of Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India. The preface of “Fanny Burney”‘s first novel, Evelina, contains a poem in praise of the author’s father, which is in fact a poem in praise of Warren Hastings.

We know that “The Wanderer” was written by Fanny Burney and not Eliza de Feuillide for two reasons. Firstly, it was written while Fanny Burney was stranded in France for 12 years whilst Eliza was living in England. Secondly, the style of writing is similar in style to letters of the time written by Fanny Burney. If anyone wants to know further details of this they can find it in the book “Jane Austen – a New Revelation”

In November 1814 she returns to France with M. d’Arblay who had come over to London to fetch her back, and leaving Alexander at Cambridge. A rough and stormy journey to Calais in an open boat. Fanny suffered severely from seasickness and was carried off the boat but then M.d’A suffered the near fatal accident mentioned above. Fanny described the accident in detail in a letter to Princess Elizabeth ending with

“Mr d’Arblay soon raised himself, for his head, I praise God! Was uninjured: but his breast felt bent double, and he could not stand upright…he was put to bed, blooded, and attended by the military surgeon of Calais for several days. We then slowly reached Paris where I at least had the solace to see him under the care of the Prince of Surgeons Dr Larrey.”

In February 1815, M le chevalier d’Arblay, now Maréchal de Camp, and second lieutenant de la Garde du Roi, was stationed with an artillery company under the Duc de Luxembourg at Senlis. Fanny was preparing to join him there when the news of Napoleon’s escape from Elba came. See Flight from Paris to Brussels for the next episode.

My Trip to Paris with my mother

July 2009

My 89 year old mother and I had gone to see rue de Miromesnil in 2009 and had written about it in a booklet which we called Food and Friends that she and I put together about her 6-week-long visit to England and France.

28 July – Tuesday – Liz and Hilary take a taxi to Rue de Miromesnil to look at the house where Fanny Burney lived from 1802. Although not our preferred first call in Paris, we set out on a hot final morning.

‘To account here for our first preference of that street is a story- an alluring account by Fanny Burney (Mme. D’Arblay) as quoted in vol. 5 of her Journals (1803), ed. Joyce Hemlow. What did the word Miromesnil mean, we wondered. A Napoleonic battle? Anyway, not a victory or we would know. A different French accomplishment, perhaps? No, we would have heard. An actor of note? We left it at that for the moment but later from the internet learned that the letters patent naming the street were created in 1776 and named it after the Marquis de Miromesnil (1723–1796) who was a Keeper of the Seal, deputy to the Chancellor of France (Minister of Justice) from 1774 to 1787. He abolished the use of torture during the interrogation of the accused.

We viewed the middle-road as wide and flat as the d’Arblays must have known it. Footpaths are similar, and clean as an English whistle. Hilary and I sat outside the street-door to the d’Arblay building, looking across at the Hotel Malmaison… Five other “rues” came into our one, not far along. We drank French coffee in the sunshine and ate a tasty salad.’

Even more gripping to our imaginations was the lower gateway between two four-storey buildings, which lead Fanny from her three- storey window to write in joy of the view and the perfume of flowers from the next street through... 8 Rue de Miromesnil.

The d’Arblay apartment was a thing for close description in itself. Three stories up, where Fanny could not climb for her first post-travel week, but her husband’s contacts with such of his old aristocratic friends as had survived the revolution, brought numbers of them staggering up the stairs to pay courtsey to his wife. They knew her, like thousands of others, as a very popular novelist – the newest and best of the kind.

The most evocative description was of the departure of her husband, General d’Arblay an officer of the Body Guard of the King, on March 19 1815 when he went to join the Guard who were to protect the King Louis 18 fleeing from Buonaparte (see Flight from Paris to Brussels).

My Trip to Paris

May 2022

In May 2022, I went back to Paris to walk around the streets that the d’Arblays had lived in. How different is my trip to Paris from Fanny’s in 1802 with a strange child and her son. Or any of the other traumatic trips she or her husband made. Fanny quotes a letter from her husband about his trip, in a letter to her father November 12 1801:

“He was 3 days without food – the fury of the Storm overturned his Basket of provisions – and his bottle of wine was broken – He was called up in the middle of the night, with cries that the ship was driving over the anchor – he was then sick to death – but instantly cured, and sprung up, and worked harder than any sailor – till the ship got into Port – 6 days and a half out of 8 were spent in storm.”

I was on my own and was travelling from St. Pancras, London to Paris on Eurostar. It took 2 hours and 25 minutes. Being 80, I was able to request assistance so was swept through Covid and passport control, no queuing, no problems and when the time came, taken straight to my seat.

Monceau to Tuileries

None of the d’Arblay buildings is still there but the streets are. I started at Parc Monceau. On Sunday morning the outer perimeter becomes a joggers’ circuit but I managed to get across the path without being knocked down. It is a beautiful garden and provides a pleasant outside area for many Parisians. There isn’t the clean air that the d’Arblays enjoyed . Rue de Monceau (formerly de Cisalpine) was fashionable in the later 19th century when homes for Jewish banking families such as Rothschild, Ephrussis, and Camondo were built.

I walked down Avenue de Messine, a long straight, wide road to Boulevarde Haussmann where Rue de Miromesnil joined.

Since visiting Rue de Miromesnil with my mother, I have learned more about the location from the biography of Fanny Burney by Kate Chisholm. Houses on right-hand side of street moving away from the river were given even numbers; those on the left, odd numbers. The Hôtel Marengo (their building in which their apartment was) at No. 1185 is no more, but it would have been close to where the rue de Penthièvre now crosses the rue de Miroménil.

Both Princesse d’Hénin and Comte de Narbonne (Madame de Staël’s former lover), their friends from Juniper Hall lived in the same street. Mme d’Hénin lived in a small apartment almost opposite to the d’Arblays and Narbonne lived at 1200 (opposite side and further from the Seine).

At the end of Rue de Miromesnil, on Place Beauvau, there were many uniformed police who were guarding the residence of the Minister of the Interior. One street leading into Place Beauvau was entirely closed (did he need so much protection, the election is over?). I was able to continue in the d’Arblay footsteps by going down Avenue de Marigny with Elysée Palace on one side. Into the Champs Elysée. The fashion houses now in the area would interest her.

It was midday when I reached the Place de la Concorde which was packed with tourists. Then along through the Jardin des Tuileries and the Place du Carrousel to the Louvre. It took me nearly an hour to walk from Parc Monceau to the far side of the Louvre. Fanny was clearly a keen walker but it must have become more difficult for M. d’Arblay to enjoy their favourite walk through the Tuileries.

Entrance to Parc Monceau

Perimeter of Parc Monceau

Parc Monceau

Hotel Ephrussi 81 Rue de Monceau formerly home of the Ephrussi family – Edmund de Waal wrote about them in his book “Hare with Amber Eyes”

Coffee at this café looking across to the entrance of Parc Monceau and past the roadworks to Rue Monceau

Looking down Rue de Miromesnil towards Place Beauvau from Rue de Penthiévre. D’Arblay apartment on right hand side of picture.

Holiday Inn on corner of Rue de Miromesnil and Rue de Penthièvre – M. Narbonne lived around here

Where Princess d’Hénin lived in Rue de Miromesnil

Place Beauvau – residence of Ministère de l’Intérieur

Jardin des Tuileries – the Palace was burned by the Paris Commune in 1871.

The triumphal arch is still in the Jardin des Tuileries

Passy

Passy is no longer in the country outside of Paris, it is now part of the 16th Arondissement. I was able to take a bus along the Seine on l’avenue du Président-Kennedy to the stop for Radio France. Then walk up a short street at the time blocked to cars by an enormous truck. On reaching the top of the street I was in rue Raynouard (formerly rue Basse) just where the d’Arblays had lived. Fanny says they entered their house from the top which would mean that it was on the lower side of the current street. On that spot is a Museum dedicated to Balzac who had lived in a house there in 1840. It had a wonderful view down to the Seine and over to Paris.

Radio France corner of Rue du Docteur Germain Sée and l’avenue du Président Kennedy

Looking down from Museum Balzac to the garden

Rue Raynouard

Looking down to the Seine from Rue Raynouard