London from 1818 - 1840

Fanny gradually recovered enough from the death of her beloved husband to be persuaded by her son Alex to move from Bath to London. Alex wanted to be near libraries, “celebrated people” and “scientific friends”. Fanny agreed but requested a dwelling place near parks and garden “free from dust or carriages” with fresh air from flowers and fields.

11 Bolton Street, Piccadilly 1818

She arrived at her brother, James’s place in James Street, Buckingham Gate on October 2 1818 and in a few days moved to the new home for herself and Alex at 11 Bolton Street Piccadilly. Joyce Hemlow writes in her The History of Fanny Burney:

“Bolton Street had been chosen for its proximity to Green Park, Hyde Park, and St. James’s, with the advantage also of the ‘spacious gardens of Devonshire House & Lansdowne’ with those of the Duke of Portland’. The street was clean, quiet and close enough to Buckingham gate for James and his wife to visit her on their morning strolls. Fanny in her turn sometimes took morning walks to James Street. On any quiet morning in November 1818, she used to set out in her widow’s bonnet, black gloves and attire of the deepest black, accompanied by the dog Diane (see the post on Ilfracombe) and the ’Squire of Dames’…The little group could be seen winding its way along the gravel paths of Green Park or sometimes farther afield into the quiet areas of Hyde Park or sometimes near by in Berkeley Square.”

She had a famous visit from Sir Walter Scott who was brought to visit her by the poet Rogers. Sir Walter, in his Diary for November 18, 1826 writes:

“Introduced to Madame d’Arblay, the celebrated authoress of ‘Evelina’ and ‘Cecilia’, an elderly lady with no remains of personal beauty, but with a simple and gentle manner, and pleasing expression of countenance, and apparently quick feelings. She told me she had wishes to see two persons – myself, of course, being one, the other George Canning. This was really a compliment to be pleasant with – a nice little handsome pat of butter made up by a neat-handed Phillis of a dairy-maid, instead of the grease fit only for cart-wheels which one is dosed with by the pound. I trust I shall see this lady again.”

Fanny records that she told Sir Walter the story of the wig of the peruquier next door in Poland Street when she was a child. (See Poland Street Post)

Dr. Burney’s Memoirs

By now Fanny had time to go through her father’s papers including twelve closely written cahiers of his Memoirs.

“The enormous load of Letters, Memoirs, documents, mss: collections, copies of his own Letters, scraps of authorship, old pocket Books filled with personal & business memorandums, & fragments relative to the History of Musick, are countless, fathomless!”

Working on these papers occupied her for many years and it was not until 1832 when she was 80 years old, that “Memoirs of Doctor Burney” appeared in three volumes. Sadly it received the most adverse criticism both public and private. The Burney family didn’t like some of the accounts of their heritage, Mrs Delany’s family thought she had disparaged their aunt by suggesting that she was a pensioner of some sort of the Duchess of Portland. The result of a long, arduous, faithful attempt to bring her father and his charm and talents and connections into biographical form, was both a failure to do this but also drew disparagement of her own literary style. Fanny’s friend Bishop Jebb, while hinting at the defects, praised her work:

“Much as we already know of the last age, you have brought many scenes of it, not less animated than new, graphically before our eyes; whilst I now seem familiar with many departed worthies, who were not before known to me, even so much as by name”.

The poet Southey must have pleased Fanny, when he wrote to Alex saying,

“Evelina did not give me more pleasure, when I was a schoolboy, than these Memoirs have given me now; and this is saying a great deal. Except Boswell’s, there is no other work in our language which carries us into such society and makes us fancy that we are acquainted with the persons to whom we are there introduced.”

Revd Alexander Charles Louis Piochard d’Arblay (1794 – 1837)

Fanny was 42 when her only child, Alexander, was born on December 18, 1794. A precious child, he was greatly loved by both his mother and his father. As he grew, he showed every sign of cleverness which was encouraged by his parents who both tutored him. M.d’Arblay started him in the

“rudiments of Mathematics, & he made a progress in arithmetic really surprising, but his little head worked so constantly, that he solved, or invented, difficulties in the night, instead of sleeping…” So time spent on arithmetic had to be limited but “Latin, French, writing, Geography, etc. went on smoothly, while History, English, orthography, & to my best ability, Religion, fell to my share. We had every reason to be content with our little scholar…”

He was later taught by the village schoolmaster and then at a day school in Paris, where he started by being top of his class but he learned that he was more popular if not so successful and he adopted the approach that a few weeks of study before exams was enough. A form of idleness and lethargy set in which remained with him all his life. Agony for his mother. He went to Cambridge, a six foot tall student. Mathematics continued to fascinate him and he obtained a First-Class degree in Mathematics (becoming a Wrangler), after which he was appointed a Fellow of Christ College Cambridge, which paid him a generous stipend his entire life. He had a remarkable ability to learn quickly and recite from memory long poems, and was obsessed with chess (which he frequently played with his uncle, James, a renowned chess player).

He was ordained as a Church of England deacon in 1818 and as a priest on 11 April 1819 in St. James’s Piccadilly. In the summer of 1821 he spent three months walking in Switzerland with other clever young men. It was not until 1824 that he obtained a living as curate at the Camden Town Chapel responsible for parish duties over a wide district (80,000 people Fanny said) with £200 a year. Fanny was not sanguine about this career and said in a letter to her sister “It is not his capability that I can doubt – that would be affectation, but it is his absence and his carelessness.” She had reason to be concerned. He remained at the Camden Town Chapel until 1836 when, according to his aunt, the parishioners wanted him to leave. He was then briefly at Ely Chapel, Ely Place in High Holborn.

He met Mary Anne Smith and became engaged to her but died from tuberculosis before the marriage.

Depression and indolence oppressed him most of his adult life, maybe from failing to achieve the success he and his mother expected of him. His father had offered him a life in France in the military but he chose to stay in England and to go to University. It was a most unfulfilled life, even down to marriage and caused Fanny much sadness, though she was unfailing in her efforts to help and support him. Mary Anne Smith remained with Fanny to the end.

1 Half Moon Street 1828

Joyce Hemlow, in her Biography of Fanny Burney writes:

“In 1828 Alex, dissatisfied with his accommodation in Bolton Street, persuaded his mother to move to 1 Half Moon Street, where he could have a large and well-lighted study. It was opposite the Green Park and still near the squares that Fanny liked for walks and fresh air. She was still within half an hour’s summons of the ‘gracious & beloved Princesses and easily accessible to members of the family…Marianne Francis used to tell of typical evenings in Half Moon Street with Madame d’Arblay talking ‘in her animated, handclasping, energetic French way’, telling her long curious stories till she is quite hoarse, and dr Mama fast asleep but jumping up every now & then in her sweet way, to fall in with the current of the remarks, answering in her sleep…”

The house was on the east side of Half Moon Street on the corner with Piccadilly with a linen draper’s shop in the ground floor. Fanny’s sitting room was the front room over the shop.

112 Mount Street – August 27 1837

Alex died on January 19, 1837, a devastating blow for his mother. She called it

“this most mournful- most earthly hopeless, of any and of all the years yet commenced of my long career” and she goes on to describe it as “this last irreparable privation, and bereavement of my darling loved, and most touchingly loving, dear, soul-dear Alex.”

Alex’s fiancé, Mary Ann Smith offered to come and live with her. As she now had acquired Alex’s large library, manuscript works and papers as well as all her own she needed a new home. She moved to Mount Street which was still near the parks, and to her physician’s astonishment she was able to resume her walks in Berkeley Square. Mary Ann came to live with her in March, providing some greatly needed company. A few remaining old friends called and mentioned the faithful Mary Ann playing gently on the piano.

29 Lower Grosvenor Street

29 Lower Grosvenor Street

In January 1839 she moved here.“I am bodily better certainly but worn with removing at this season – in my shattered state & in this month (when both Alex and her beloved sister Susanna died) – this baleful – yet let me hope blessed month!” She died in January the following year. She told the poet Rogers that she repeated the lines from Mrs Barbaud’s Life to herself every night before she went to sleep.

Life! we’ve been long together,

Through pleasant and through cloudy weather;‘Tis hard to part when friends are dear;

Perhaps ‘twill cost a sigh, a tear;

Then steal away, give little warning,

Choose thine own time,

Say not Good Night, but in some brighter clime

Bid me Good Morning.

My walk through Mayfair

Buckingham Palace

I set off on a Sunday morning to walk from James Street, Buckingham Gate where brother James lived across to 11 Bolton Street.

From the map of the area in 1800, one sees that James Street which is now called Buckingham Gate and faced straight across to St. James’s Park. On the map it looks as though there was some sort of Barracks on Birdcage Walk, but the present Wellington Barracks which lies between Birdcage Walk and Petty France and up to Buckingham Gate was not built until 1833. The Barracks are 300 yards from Buckingham Palace, allowing the guard to be able to reach the palace very quickly in an emergency.

In 1818 Buckingham Palace was not the official residence of the King, that was St. James’s Palace but there was a palace, called Queens Palace which became the current Buckingham Palace. George III bought Buckingham House in 1761 for Queen Charlotte to use as a comfortable family home close to St James’s Palace, where many court functions were held. Buckingham House became known as the Queen’s House, and 14 of George III’s 15 children were born there.

So I walked across St James’s Park at the end nearest Buckingham Palace, crowded, as it was a Sunday morning with families enjoying the space and outside interests. Past the ducks in the lake which is described in the map as a Canal. The history is well described on the website of the Royal Park “In the 1820s, the park got another great makeover. It was remodelled in the new naturalistic style. The canal became a curving lake. Winding paths replaced formal avenues. Fashionable shrubberies took over from traditional flower beds. Buckingham House was enlarged to create a new palace with a vast arch faced in marble at the entrance. And the Mall was turned into a grand processional route. The work was commissioned by the Prince Regent, later George lV. It was part of a huge project that created many of London’s best-known landmarks, including Regent’s Park and Regent’s Street. It was overseen by the architect and landscaper, John Nash. He produced the designs in 1827 and within a year the work on St James’s Park was finished”. The park you see today is still very much as Nash designed it and there have been only small changes since. Traffic was allowed to use The Mall in 1887. The Marble Arch outside Buckingham Palace was moved to the junction of Oxford Street and Park Lane in 1851. The area outside Buckingham Palace was remodelled between 1906 and1924 to make space for the Victoria Memorial. An elegant suspension bridge was built across the lake in 1857 and was replaced 100 years later by the concrete one we see today.”

11 Bolton Street

Connaught Hotel

Bolton Street

I walked across the Mall which was closed to traffic but packed with tourists and on up through Green Park on the path beside Lancaster House to Piccadilly, the Queen’s Walk, coming out beside Green Park tube station. Crossing Piccadilly to Bolton Street and up to number 11 where there is a blue plaque honouring Fanny Burney. It took me 12 minutes to get from one place to the other. I suspect it would have taken a great deal longer for the Burneys but perfectly manageable for their daily walks. Bolton Street is now quite a quiet one-way street from Curzon Street to Piccadilly, right in the heart of Mayfair. There is so much building work going on that it is unlikely to remain the slightly dusty, rather old-fashioned street it is at the moment.

Up to Curzon Street and right around the street to Berkeley Square. Another London square with glorious tall plane trees. A noticeboard with its history revealed that George Canning had lived in the Square. So it was no coincidence that Fanny Burney told Sir Walter Scott that he and George Canning were the two visitors she would most want.

112 Mount Street

Following up the west side of Berkeley Square, I came to Mount Street which I turned in to, walking towards the Connaught Hotel. (It had opened in 1815 as the Prince of Saxe Coburg Hotel.) Right opposite the hotel was number 112 Mount Street where Fanny had lived and beside it set back behind a lovely paved and treed area was the Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception, Farm Street. Fanny was no longer living there when the church was built in 1844.

29 Lower Grosvenor Street

Grosvenor Square was only a few hundred metres away and that was my next stop. Fanny had spent time in Grosvenor Street which was further east towards Bond Street but her place must have been on the corner of Davies Street. There is now a modern commercial building there. It was only a short walk back down Davies Street back to Berkeley Square.

Half Moon Street

Two streets away from Bolton Street. This time Fanny was on the corner of the street, on Piccadilly, looking over Green Park. Today Piccadilly is full of noise and very busy with cars and buses. Half Moon Street had a poor reputation in the 20th century and it still has a trace of seediness. But it will soon be filled with modern buildings some of which are already underway, as it is in such a central position for the West End of London, now the home of hedge funds and venture capitalists.

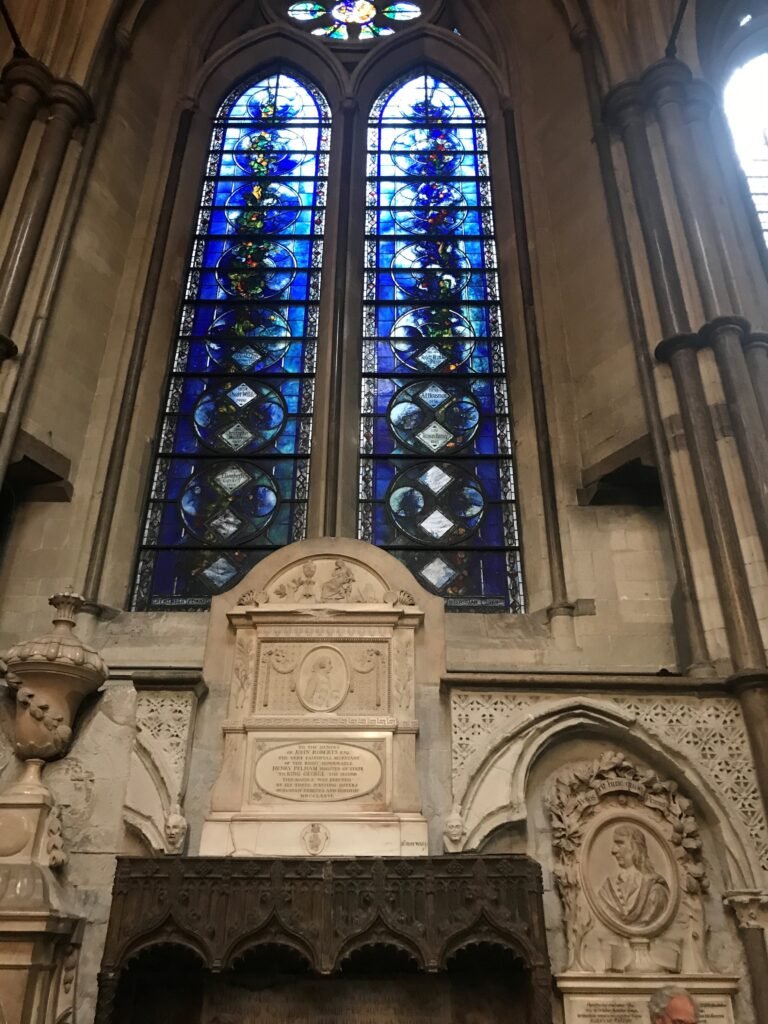

Memorial panel in new Poets Corner in Westminster Abbey unveiled in June 2022

Birdcage Walk looking towards the Wellington Barracks

Buckingham Gate – formerly James Street

Corner of Buckingham Gate looking towards Buckingham Palace

Crossing the Mall into Green Park

Buckingham Palace

11 Bolton Street there is a blue plaque

11 Bolton Street

11 Bolton Street

Church of the Immaculate Conception – entry to Farm Street Jesuit church

112 Mount Street

Grosvenor Square -where Grosvenor Street joins

Corner of Davies and Grosvenor Streets – where 29 Grosvenor Street was formerly

Grosvenor Street looking towards Bond Street

Berkeley Square

Berkeley Square

George Canning (1770-1827) became Foreign Secretary whilst at No. 50 Berkeley Square.

Berkeley Square

Piccadilly looking at Green Park

Half Moon Street

Half Moon Street

Piccadilly corner with Half Moon Street - Fanny’s flat on the first floor facing the Park