Joigny

ALEXANDRE-JEAN-BAPTISTE PIOCHARD D’ARBLAY (born Joigny, France 1748 died Bath England, 1818; married Frances Burney 1793)

Throughout the marriage, lack of money and the means of getting it occupied their thoughts and motivated their activities, justifying Dr Burney’s anxiety about his daughter marrying a penniless, out of work, émigré soldier. For Fanny her energies went to writing to earn an income and for Alexandre his hopes were getting compensation for lost land, or an army pension from the French state or another army role.

It was said that Alexandre was born in the chateau, the current one known as Château of Gondi which was built between 1569 and 1613. At 14 he went to military school in Strasbourg. His army records show that by the following year he had become a lieutenant in a regiment in Toul, north-eastern France, and progressed to become a major in La Garde Nationale Parisienne in 1789. He was a chevalier de Saint-Louis, 26 Oct. 1791; Lieutenant Colonel,1789; Adjutant General Colonel 1 Feb 1792 to General Marquis de la Fayette. On 22 July 1792 he was named field marshal (maréchal de camp) but did not receive his commission because he deserted with Lafayette and fled to England after the rise of Maximilian Robespierre. He is authorized to travel to Santo Dominigo on January 27, 1802, and he was retired on May 2, 1803.

During the first Restoration, he became second lieutenant of artillery in the bodyguards of Louis XVIII, Compagnie de Luxembourg June 1 , and he was confirmed Field Marshal on July 14, 1814.

Set on the Yonne river between Sens and Auxerre in Burgundy. The ancient city of Joviniacum would have been the seat of a Roman villa. It was part of the lands of the Dukes of Burgundy who would lease areas to vassals who in turn would earn an income from local farmers. It was the scene of many a battle – religious or territorial wars. Dauphin Charles VII against the Duke of Burgundy or Anglo-Burgundians against Charles VII in 1423, at the Battle of Cravant; in 1428 Charles VII visited Auxerre with Joan of Arc. The comté de Joigny at this time was Guy de la Trémouille who favoured the English and so fatally disagreed with the inhabitants of Joigny who besieged him in his own castle after the capture of Joigny in 1429 by the English. The marshal of Chastellux or Toulongeon had wanted to protect him; but he still perished in 1438 by the hand of his vassals suddenly armed with pitchforks, sticks and mallets, which made them give the nickname of Maillotins. The mallet appears, since then, in the arms of Joigny.

Joigny acquired a bridge from the twelve century at least. It connected the castle and town to the prosperous farm lands and wine growing areas. The Count drew income from the toll and the viticulture contributed to enrich the city.

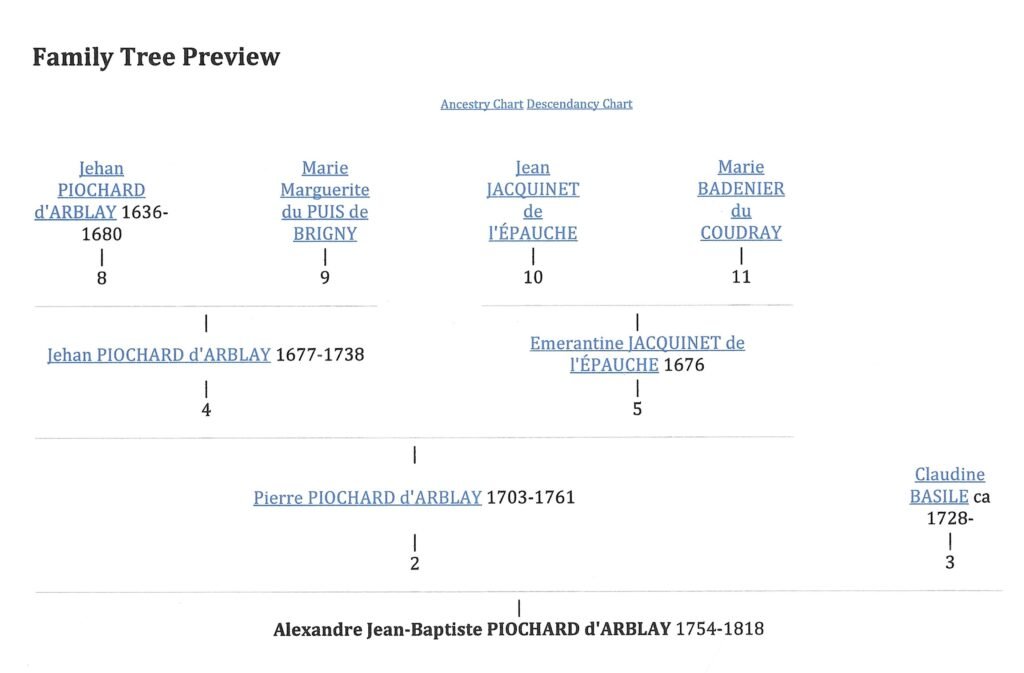

The Piochard d’Arblay family were landowners and farmers. In one history they are named along with the Rageon du Bouchet family as contributing in the eighteenth century to the dismemberment of the county lands which were sold along with those of all other noble or religious owners. Arblay is an area about 15 miles west of Joigny but members of the family had land in various parts south of Joigny.

On his mother’s side, it was the Basile (Bazille) family who were townspeople. They may even have owned the Duc de Bourgogne hotel.

Selected Papers of the Consortium on the Revolutionary Era (2020).

“the ci-devant Comte d’Arblay, whose constitutionalist sensibilities disqualified him from service in the ultra-royalist émigré armies then congregating along the Rhine. An urbane captain in the Old Regime army, he had served in the Parisian National Guard from September 1789 and then as Lafayette’s adjutant- general in the Army of the North. The two friends had been on duty at the Tuileries on the fateful night in June 1791 when the royal family was seized en route to France’s eastern frontier, and they both deserted in August 1792 after being proscribed by the Jacobins back in Paris. D’Arblay headed north on 16 August. Three days later, Lafayette and twenty-plus members of his general staff fled east, where they were recognized and arrested near Rochefort, their claim to noncombatant status and the right to transit tersely denied. Lafayette spent the years that followed in an Austrian prison, while d’Arblay made his way to Juniper Hall.

Like each of the 130 000-or-so French men and women who ended up on the General List of Émigrés, however, d’Arblay had been condemned to civil death, deprived of his property, and banished in perpetuity. As per the sprawling émigré code enacted by the National Convention in the spring of 1793, absentees caught back in France were treated as traitors, regardless of the circumstances of their emigration, and were accordingly denied the right to either trial by jury or appeal. Whether relegated to military tribunals as armed “rebels” or criminal courts as unarmed “deserters,” they were to be executed within twenty-four hours.

During the preliminary peace in late 1801, d’Arblay scrambled to secure his family the necessary passports in London. But when his son fell ill, he decided to make a quick solo trip.” across the Channel to reconnect with relatives and claim his pension for serving Louis XVI before and during the early years of the Revolution. Cleared of his émigré status, d’Arblay needed to amend his military record, making the case that he should be treated not as a deserter, but an officially discharged—and thus pensionable—veteran. But even so, according to the Ministry of War, he fell just shy of the 25-year service benchmark needed to qualify for a full pension, and was told he would have to complete one final tour of duty. When Burney welcomed him back to England in January 1802, she was distressed to learn the now middle-aged and out-of-practice soldier would be deployed to Saint-Domingue as part of the campaign to reinstate metropolitan authority—and, it soon became clear, the institution of slavery—in France’s Caribbean colonies. General Leclerc’s mission was not only dangerous, but morally suspect to abolitionists like Burney. As d’Arblay made the necessary expenditures to equip himself for battle, blowing a hundred louis the family could not spare on gear, she set aside any qualms she may have had about Napoleon’s true intentions, assuring a friend that the mission was aimed solely at “restor[ing] order in the…colonies.” On one principle, however, the couple refused to bend: their shared devotion to their homelands, which put d’Arblay in an untenable position as he prepared to re-enlist for France.

Ultimately, d’Arblay’s conflicting loyalties combined with his political naivety to derail his deployment. Before leaving England in early 1802, he wrote directly to Bonaparte to relay his appreciation for the opportunity to serve the Republic, before adding a deal-breaking stipulation: he refused to take up arms against the country that had “nourished” his family through nine years of exile.”

Equally dogged by misfortune was his attempt to recover lands and inheritance from the family estates in Joigny, Burgundy. He heard from his mother’s brother, Jean-Baptiste-Gabriel Bazille, that £1,000 would be available to him immediately if he signed, sealed and witnessed the rights to his property to his nearest surviving relation in France in a country not at war with France so he applied for a passport to Holland. It was all fruitless and he didn’t retrieve any part of the money.

In a letter of August 10, 1797 Fanny writes after hearing of the death of Alexandre d’Arblay’s brother

“He is now the last of a family of seventeen, and not one relation of his own name now remains but his own little English son. His father was the only son of an only son, which drives all affinity on the paternal side into fourth and fifth kinsmen.

On the maternal side, however, he has the happiness to hear that an uncle, who is inexpressibly dear to him, who was his guardian and best friend through life, still lives, and has been permitted to remain unmolested in his own house, at Joigny, where he is now in perfect health, save from rheumatic attacks which though painful are not dangerous. A son, too, of this gentleman, who was placed as a commissaire-de-guerre by M. d’A during the period of his belonging to the War Committee, still holds the same situation, which is very lucrative, and which M.d’A had concluded would have been withdrawn as soon as his own flight from France was known.

The little property of which the late Chevalier d’Arblay died possessed, this same letter says, has been “vendu pour la nation” because his next heir was an émigré; though there is a little niece, Mlle, Girardin, daughter of an only sister, who is in France…

Some little matter however what we know not, has been reserved by being bought in by this respectable uncle, who sends M. d’A word he has saved him what he may yet live upon, if he can find means to return without personal risk, and..

The late chevalier, my M.d’a. says, was a man of the softest manners and most exalted honour; and he was so tall and so thin, he was often nicknamed Don Quixote, but he was so completely aristocratic with regard to the Revolution at its very commencement, that M.d’A. has heard nothing yet with such unspeakable astonishment as the news that he ‘died, near Spain of his wounds from a battle in which he had fought for the Republic! — How strange, says M.d’A is our destiny! that that Republic which I quitted, determined to be rather a Hewer of wood and Drawer of water all my life than serve, he should die for!’…In the period, indeed, in which M.dA. left France, there were but three steps possible for those who had been bred to arms – flight, the guillotine, or fighting for the Republic. ‘The former this brother,’ says M.d’A says, ‘had not energy of character to undertake in the desperate manner in which he risked it himself, friendless and fortuneless, to live in exile as he could. The guillotine no one could elect; and the continuing in the service, though in a cause he detested, was, probably, his hard compulsion.”

In 1802 M. d’Arblay took his wife and son to Joigny to be introduced to his family. Fanny wasn’t particularly happy for two reasons; she did not like the endless socialising, and she did not like small towns (like Kings Lynn where she had been born and gone as a child).

“M. d’Arblay has so many friends, & an acquaintance so extensive, that the mere common decencies of established etiquette demands, as yet, nearly all my time! & this has been a true fatigues both to my body & my spirits”.

Young Alexandre, on the other hand found Joigny and its inhabitants exciting. One day he rushed home to tell his mother a “great secret”: he had been kissed by Napoleon’s brother, Colonel Louis Bonaparte, (afterwards King of Holland) whose regiment was stationed nearby. She also saw the sites of burned châteaux such as the one in the nearby village of Cézy belonging to the ci-devant Princess de Baufremont.

Fanny had met Princesse de Beaufremont in Paris where she spent the winters but she still spent the summers at Cezy and Fanny expressed a wish to see her in both places. Mde de Beaufremont now resides in a small Villa she has preserved from destruction…

“She was one of those who suffered the most severely in the Revolution, though from no possible provocation beyond her high rank, and magnificent possessions. She had a Chateau in Franche comté, nearly as large & superb as that of Versailles – which a party of Brigands burnt to the ground, with all its pictures, goods, & valuables!” Fanny describes her as having ”a kind of high bred serenity of manner, extremely engaging, with a peculiarly engaging tone of voice, & pronunciation. She has remarkably large, soft, fine eyes, & is still handsome, in defiance of a corpulency that, had she less of ease & elegance in her deportment, would be the greatest disadvantage…”

My Trip to Joigny, Cézy and Arblay

Joigny is a very pretty town rising up from the Yonne river. But like many rural towns in France, it is “dying”. The young people are moving to bigger cities leaving only the elderly behind. However, Joigny is only one and a half hours from Paris by car or by train and so they are hoping that with efficient internet connections (fibre optic cables are being laid), young people with growing families will move there. Certainly, Parisians are buying second homes in the area.

The surrounding lands are vast and Burgundy supplies much of the grain required, and it will be even more in demand since the war in Ukraine has reduced their supplies. This is not an area for cattle so there are few animals in the fields.

Côte Saint-Jacques wine -. The most northerly vines in Burgundy grow on the slopes of the Côte Saint-Jacques they look down over Joigny, on the right bank of the River Yonne.

The first written evidence of there being vines in Joigny dates back to 1082 and winegrowing flourished here throughout Medieval times. In 1704, Louis XIV introduced the gris wine of Côte Saint-Jacques to the court in Versailles. At its height, the vines here covered 574 hectares. After phylloxera decimated the trade, it wasn’t until 1970 that it was revived by passionate winemakers determined to carry on local tradition.

When we had a house near Joigny, my favourite drink was a glass of the local pinot gris while sitting outside on a warm evening.

It was a great pleasure to go back to Joigny on my Fanny Burney trail. I came down from Paris on the train, one and a bit hours these days. Maryly met me at the station as she is staying nearby in the Puisaye and we began our exploring. We went to the Mairie to see if they had the Baptism Certificate for Alexandre d’Arblay. My mother had been able to get one, but it got lost after she died and now the records have all been transferred to Auxerre. But I did remember that there was reference to the house of the Bazille family in Rue d’Étape which is still there.

We also toured the three large churches. There is a plaque dedicated to members of the Piochard family on the wall of the Eglise St. Jean and it is probably in this church that Alexandre was baptised. Also in this church is the famous 13th century recumbent statue of Countess Aélis (of Joigny) with an allegory on carelessness (oriental legend of Barlaam and Josaphat). After a delightful lunch in a small café at the top of the hill, we set off for Cezy. There is no chateau in Cezy and there seems to be little going on in the town except for roadworks but the drive to it along the Yonne is a pleasure. From Cézy we went on the Arblay. Again we went through lush countryside. In Arblay, itself there were only a couple of houses, one recently sold and a dilapidated barn. The tradition is for farmers to live in the villages, not on their farmland which they would tend each day.

-

Looking across the Yonne from Rue d’Étape where the Bazille family lives

-

House on left with green shutters where the Bazille family still live

-

Chateau de Gondi where Alexandre may have been born

-

The back of the Chateau of Gondi which faces the river

-

Eglise St. Jean

-

Tomb of Countess Aélis in Église St. Jean

-

Ancient wooden house in Joigny

-

Typical Joigny House

-

Our Lunch Spot

-

Cézy

-

Lavoir at Cézy

-

Cézy

-

Maybe this was the Chateau of Cézy. Balzac used this chateau as a reference to his characters in La Comédie humaine.

-

Burgundy countryside close to Arblay

-

Arblay, Burgundy

-

Arblay, Burgundy

-

Arblay, Burgundy