Bath

Fanny said that she visited Bath 5 times. Some were more significant than others and it was where she chose to be buried with her husband and son. Her first visit was with her father on the way back from Bristol Hotwells in mid 1767. Nothing seems to be known of their time in Bath; not where they stayed, nor for how long. She would probably have read Smollett’s novel, ‘The Expedition of Humphry Clinker’ published in 1771 in which the elderly Matthew Bramble complains about the deterioration of Bath saying that it had

“become the very centre of racket and dissipation…Every upstart of fortune, harnessed in the trappings of the mode, presents himself at Bath…Clerks and factors from the East Indies, loaded with the spoil of plundered provinces; planters, negro-drivers, and hucksters, from our American plantations, enriched they know not how; agents, commissaries, and contractors, who have fattened, in two successive wars, on the blood of the nation…and all of them hurry to Bath, because here, without any farther qualification, they can mingle with the princes and nobles of the land.”

He is equally critical of the architecture and the lauded improvements: “The square, though irregular, is, on the whole, pretty well laid out, spacious, open and airy;…but the avenues to it are mean, dirty, dangerous, and indirect. Its communications with the baths is through the yard of an inn, where the poor trembling valetudinarian is carried in a chair…The Circus is a pretty bauble, contrived for show, and looks like Vespasian’s amphitheatre turned outside in…”

Fanny’s next visit seems to have been in 1776 or 1777 and again there is no record of it but she has included in Evelina (published in 1778) a realistic description of the place, with Evelina writing:

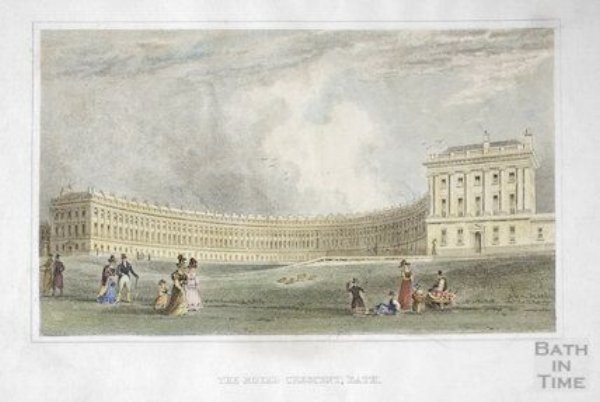

“The charming city of Bath answered all my expectations. The Crescent, the prospect from it, and the elegant symmetry of the Circus, delighted me. The Parades, I own, rather disappointed me; one of them is scarce preferable to some of the best paved streets in London, and the other, though it affords a beautiful prospect, a charming view of Prior Park and of the Avon, yet wanted something in itself of more striking elegance than a mere broad pavement, to satisfy the ideas I had formed of it.”

The third visit was in 1780, with Mr and Mrs Thrale and their daughter, Queeney and is very well documented. It took them four days to get to Bath from London and they spent the nights at Maidenhead, Speen Hill and Devizes.

Fanny in Bath

-

14 South Parade

April - June 1780

“I shall now skip to our arrival at this beautiful city, which I really admire more than I did, if possible, when I first saw it. The houses are so elegant, the streets are so beautiful, the prospects so enchanting…we were told of lodgings upon the South Parade, whither in the afternoon we all hied, and Mr Thrale immediately hired a house at the left corner. It was most deliciously situated; we have meadows, hills, Prior Park, ‘the soft-flowing Avon’ – whatever nature has to offer, I think, always in our view. My room commands all these; and more luxury for the eye I cannot form a notion of.”

No mention here of the disappointment in the Parades voiced by Evelina.

Fanny's room was at the side of the building overlooking the river, she writes of her time being taken up with “engagements, dress and work” (needlework), Church on Sundays – St. James’s for a while, then the Abbey to hear the Bishop of Peterborough.

Painting by John Charles Maggs in the 19th Century

-

23 The Circus

Lodging here was the famous Blue Stocking, Elizabeth Montagu, who was then widowed and one of the wealthiest women in England. Learned and sociable, the Blue Stockings (Elizabeth Carter was also in Bath) were renowned not only for their writing but for the quality of their conversation. “We see Mrs Montagu very often, and I have already spent six evenings with her at various houses.”She wrote when they had been in Bath three weeks. Her most intimate companion, apart from the Thrales seems to have been Augusta Byron (aunt of the poet (1788-1824) who was not born at this time).

“Sunday – We had Mrs Byron (grandmother of the poet) and Augusta, and Mrs Lee, to spend the afternoon. Augusta opened her whole heart to me, as we sat together, and told me all the affairs of her family. Her brother, Captain George Byron, is lately returned from the West Indies, and has brought a wife with him from Barbadoes, though he was there only three weeks, and knew not this girl he has married till ten days before he left it! – a pleasant circumstance for this proud family. Augusta is a very amiable, ingenuous girl, and I love her the more for her love of her sisters: she talked to me of them all, but chiefly of Sophia…”

Poor Sophia was dead before the year was out. There was considerable space taken up with accounts of Augusta’s conquest of a young soldier, Captain Brisbane, who was expected to propose. If he did, nothing came of it, because Augusta married into the navy which was fitting for the daughter of Vice Admiral John Byron (foul weather Jack). Her husband, Vice Admiral Christopher Parker, son of Admiral Sir Peter Parker and she had three sons, Captain Sir Peter Parker (killed in a battle in Maryland USA in 1814), Captain Sir John Edmund George Parker and Admiral Sir Charles Christopher Parker. There is a family vault where they are all buried in St. Margaret’s, Westminster.

Another favourite was an Irish Peer, Lord Mulgrave, captain in the Royal Navy (“his wit is of so gay, so forcible, so splendid a kind…” says Fanny), who, on one occasion after mentioning Captain George Byron and his recent marriage, turned to Fanny and called out:

“See, Miss Burney, what you have to expect – your brother will bring a bride from Kamschatka, without doubt!” Fanny replied ”That may perhaps be as well as a Hottentot, for when he was last out, he threatened us with a sister from the Cape of Good Hope.”

Mrs Thrale reported that all the sea captains would fall upon Fanny “Captain Cotton, my cousin, was for ever plaguing her about her spite to the navy”. They were taking Fanny to task in a good humoured way about the rough Captain Mirvan in “Evelina”. Augusta Byron told Fanny that her father, the admiral, often talked of Captain Mirvan, whom he regarded as a brute but he loved the novel.

Painting by John Robert Cozens 1773

-

Belvedere

“I went to the Belvedere, (a hotel) and made Mr Thrale accompany me by way of exercise, for the Belvidere is near a mile from our house, and all up hill.

The Belvidere is a most beautiful spot, it is on a high hill, (Lansdowne) at one of the extremities of the town, of which, as of the Avon and all the adjacent country, it commands a view that is quite enchanting.”

Painting is Belvedere by Walter Sickert 1907

-

Spring Gardens

Pleasure grounds laid out on the opposite side of the Avon from South Parade – were reached by ferry. One day, their dinner guest, the Bishop of Peterborough, proposed a trip to Spring Gardens “where he should give us tea, and thence proceed to Mr Ferry’s to see a very curious house and garden”.

-

Bathwick Villa

“Mr Ferry is a Bath alderman; his house and garden exhibit the house and garden of Mr Tattersall enlarged. Just the same taste prevails, the same paltry ornaments, the same crowd of buildings, the same unmeaning decoration and the same unsuccessful attempts at making something of nothing.”

One of the, ‘puerile wonders he delighted in. This was a strange device that causes the dining table to rise up through a trap door in the floor and a carved eagle to descend from the ceiling and take up the table cloth revealing a rich display of confectionary’The villa stood to the right of the approach road to the later constructed Cleveland Bridge, roughly on the sites of 10-15 Forester Road. It closed in 1790 and by 1851 was subdivided and used as a poor house. It became derelict and was finally demolished in 1897.

-

Batheaston

A few miles east of Bath, the home of Sir John and Lady Miller. In a bow window overlooking the Avon stood a Frascati vase into which, on certain Thursdays, guests were invited to drop poetical contributions which were eventually published in four volumes. Fanny writes on Thursday June 8:

“We went to Bath Easton…The house is charmingly situated, well fitted up, convenient, and pleasant, and not large, but commodious and elegant. Thursday is still their public day for company, though the business of the vase is over for this season.”Not everyone delighted in a visit to Batheaston. Horace Walpole, in a letter to the Hon. H. S. Conway, says: “I am glad you went [to Bath], especially as you escaped being initiated into Mrs. Miller’s follies at Bath-Easton” (Letters, vii. 163).

-

5 Royal Crescent

Where Christopher Anstey lived. Writer of The New Bath Guide published in 1766, not a guide, but a satirical poem in the form of letters describing and making fun of the fashionable life in Bath.

“Of all the gay places the world can afford,

By gentle and simple for pastime ador’d,

Fine balls and fine concerts, fine buildings and springs,

Fine walks and fine views, and a thousand fine things,

(Not to mention the sweet situation and air,)

What place, my dear mother, with Bath can compare?”But Fanny wasn’t at all impressed by him though she loved his Guide.“I heard but little that he said, and that little was scarce worth hearing.”He was, she said “shyly important and silently proud”. Elizabeth Montagu lived at number 16, the house in the centre of Royal Crescent at some stage. She writes “the beautiful situation of the Crescent cannot be understood by any comparison with anything in any town whatsoever”.

They had been in Bath for 3 months when news came from London of frightening riots against “Papists”. These were a reaction to the Roman Catholic Relief Bill of 1778. Whipped up by Lord Gordon 60,000 anti-Catholic objectors to the relief had marched on the House of Commons demanding a repeal of the Act. Lord Gordon was put in prison but the rioting had moved to Bath. The new Roman Catholic chapel was set alight and the Thrales packed in panic as Mr Thrale, who had voted in favour of the Bill for the relief of Roman Catholics had been targeted. Fanny wrote to her father:

“We did not leave Bath till eight o’clock yesterday evening, at which time it was filled with dragoons, militia, and armed constables, not armed with muskets, but bludgeons…We set out in the coach-and-four, with two men on horseback, and got to Warminster, a small town in Somersetshire, a little before twelve.”

Painting The Royal Crescent, by TH Shepherd

-

Queen Square

August 20 – September 10 1791

To help Fanny recover from the illness brought on by her time with the Royal household, a kind friend, Mrs Ord, offered to go with Fanny on a tour of the west of England. They reached Bath around August 20th when Fanny wrote to her sister, Susan:

“Bath is extremely altered since I last visited it. Its circumference is perhaps trebled: but its buildings are so unfinished, so spread, so every where beginning, and no where ending, that it looks rather like a space of Ground lately fixed upon for creating a Town, than a Town itself, of so many years duration.

It is beautiful and wonderful throughout. The Hills are built up and down, and the vales so stocked with streets and Houses, that, in some places, from the ground floor on one side of a street, you cross over to the attic of your opposite neighbour. The White stone, where clean, has a beautiful effect and even where worn, a grand one. It looks a City of Palaces – a Town of Hills, and a Hill of Towns.”

In a letter dated 8 September, she wrote to her sister Hetty (Mrs Burney No2. Upper Titchfield Street, Portland Place, London)

“This City is so filled with Workmen, dust, & lime, that you really want two pair of Eyes to walk about in it…Bath seems, now, rather a collection of small Towns, or of magnificent Villas, than one City. They are now building as if the World was but just beginning, & this was the only spot on which its inhabitants could endure to reside…One street leading out of Laura Place…pompously labelled Johnson Street, has in it only one house."

Fanny begged Mrs Ord not to introduce her to any new people, but she welcomed Lady Spencer (mother of Lady Georgiana Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Duncannon, (infamous for her affair with R.B Sheridan; mother of Lady Caroline Ponsonby who married Charles Lamb much to the sorrow of her cousin Charles who became 6th Duke of Devonshire and never married) and whom she had met at Mrs Delany’s. Fanny’s description of Lady Spencer included a tart comment that “she spends her life in such exercises of active charity and zeal, that she would be one of the most strikingly exemplary women of Rank of the age, had she less of shew in her exertions, & more of forbearance in publishing them.”

Fanny’s letters are full of gossip about the Devonshires and Lady Elizabeth Foster. Poor Fanny is torn by her prudery and her fascination or “pain and pleasure” as she called it.

Although never won over by Lady Duncannon or Lady Elizabeth Foster, whom Fanny was horrified to find was the mother of a little girl by the Duke of Devonshire, she was enchanted by the Duchess.“Poor Duchess! Is all I can say, if her entanglements are thus thrown about the Duke! It is generally believed her own terrible exravagancies have extorted from her a consent to this unnatural inmating of her House, from the threats of the Duke that they should else be separated! What a payment for her indiscretions – & she, at least, escaped further censure, & is allowed, even by the calumniators, to have been guiltless in point of fidelity to her Duke.”

Poor Fanny, did she learn that the Duchess was bearing a child born on February 20 1792 fathered by Charles Grey (later in 1834, Prime Minister)?Smallpox was rife and Fanny records that “The little Marquis (of Huntingdon, eldest son of the Duke of Devonshire) is as much guarded as a Prince of Wales: he has not had the smallpox, & they dare not, therefore, carry him about with them. His House, in Marlborough Buildings, is sacred; not a Tradesman is permitted to enter it; not a servant but of the family, so fearful is the Duchess of any infection’s reaching him.” Not unlike the lockdown of these days but there was no vaccine to protect them.

-

New List Item

Description goes here

My Trip to Bath

Queen’s Square

The Abbey

Royal Crescent

On a Bank Holiday Sunday in May we drove to Bath to visit and photograph the places associated with Fanny. The place was packed with people revelling in warmth and release from Covid lockdown.

First of all, we wanted to drive into Bath as Fanny had, looking up to the hills she always wrote about. Then to the places she had enjoyed. I am afraid on this sunny day she and General d’Arblay would have had a very difficult time reaching the Assembly Rooms, but they are still there. She would still have been pleased with the beautiful crescents and the houses in them which have been carefully preserved.

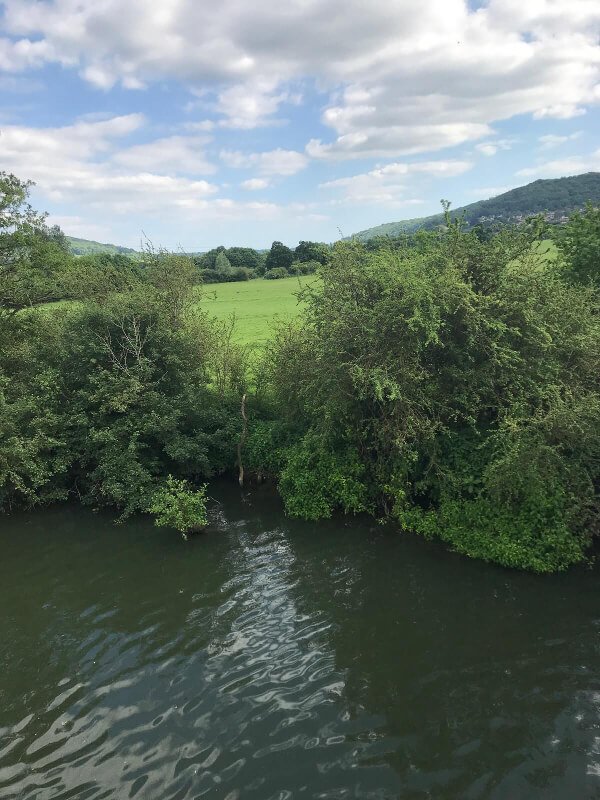

14 South Parade was our first call. Still there, looking very much as it must have done when Fanny was there in 1780, the last house in the row, looking over the Avon. On the other side of the river now is a large cricket field. An ugly church opposite on South Parade, St. John’s, was luckily for Fanny not there in her day.

Then we walked across the nearby bridge to see the Spring Gardens which Fanny had had to get to by boat. Nowadays more sports grounds but at least not built up.

No longer any sign of the much-scorned Bathwick Villa with its eccentric devices. But there is a picture of the remains of Bathwick Mill in 1960 – on the right of the picture. Queen’s Square is still lovely with well-preserved houses on all sides, now hotels, museums, solicitors’ offices and the well-tended garden in the centre.

No. 1 Royal Crescent which was the home of the widowed Henry Sandford from 1776 to 1796 has been magnificently restored and preserved as a Museum. It has been decorated and furnished as it might have been during the time when Henry Sandford lived there.

Not far from both Queen’s Square and Royal Crescent is the less salubrious Great Stanhope Street where Fanny and her husband lived when they returned from France in 1815. Fortunately, it was a very happy marriage and Fanny was truly devoted to her husband so any inconvenience of accommodation was accepted.

Thanks to a very efficient SatNav, we were able to make our way up the winding roads to Belvedere trying to imagine how Fanny and Mr Thrale managed it. Mr Thrale so fat and Fanny in the most inadequate shoes.

14 South Parade

Looking across the Avon from South Parade

Queen Square

Royal Crescent

These hot springs were used by the Romans as early as the first century

Corner of Rivers Street and Catherine Place

Rivers Street sign

Belvedere

The same street view as the Sickert painting. Then on to Batheaston and a real treat. Lovely gardens on the river though we couldn’t see the house.

Door to Batheaston House

Batheaston House

River below Batheaston

Garden Batheaston

Kings and Queens baths

No. 1 Royal Crescent

Parker Family Tomb in St Margaret’s Vault, Westminster

Memorial Sir Peter Parker

In the pious Hope of a glorious Resurrection, Pursued through Virtue, E…. and Valour.

Here lie interred the Mortal Remains of

SIR PETER PARKER Baronet. Aged XXVIII years

Captain of His Majesty’s …… Menelaus

An accomplished Officer, and Seaman, Who after landing with a part of his Crew, on the Coast of America

Defeated an Enemy supported by Cavalry and Artillery three times the number of his own Forces

And in the moment of Victory received a mortal Wound under which he continued to direct his

Men to follow up their triumph, until sinking under its fatal result. He fell into the arms of the companions of

his Glory and bravely surrendered on the field of battle, his own gallant Spirit to the Mercy of Heaven.

He was the lineal descendant of three distinguished British Admirals of whose Virtue and Valour

he was alike the Inheritor. His great Grandfather was Admiral Christopher Parker. He was the

eldest son of Admiral Charles Parker, whose father was the late Sir Peter Parker Bart of B….

Hall Essex Admiral of the Fleet, and his maternal uncle was the Honourable Admiral Byron.

After fifteen Years of active and intrepid toil in the service of his country emulating the Heroism

of his Ancestry, he thus gloriously closed his earthly Career, August….

The Officers and Crew of His Majesty’s Ship Menelaus, on their return home in testimony of

their deep affliction of the fall of their beloved Commander, and of their affection for his

Memory, have erected this Monument, as well to commemorate their grief, and reverence for

those Virtues which so justly endeared him to his Ship’s Company, as to attest to future times

their admiration of that

Heroic Valour which distinguished him in Life, and ennobled him in Death..

STAT SUA CUIQUE DIES; BREVE ET IRREPARABILE TEMPES

OMNIBUS EST VITAE; SED FAMAN EXTENDERE PAUTIS

HOC VIRTUTIS OPUS. ……VIRG.

My trip to St Margaret’s Vault

One night, while listening to “Hornblower and the Atropus”, one of the Horatio Hornblower novels written by C.S. Forester, I was amazed to hear the name Parker. Rear Admiral William Parker had become Hornblower’s commanding officer replacing the much admired Cornwallis, a poor replacement in Hornblower’s opinion.

Here is a quotation from one of the very fine papers from the C.S Forester Society:

“Rear Admiral William Parker took over from Pellew as commander of the Inshore Squadron off Brest and therefore he became Hornblower’s commanding officer. He flew his flag from HMS Dreadnought. Hornblower’s biographer referred to the “extensive Parker clan” because so many Parkers had been admirals and captains “none of them especially distinguished”. Hornblower sent him reports of his observations of the French ships blockaded in Brest. When Hornblower met Parker on his flagship, the difference between him and Cornwallis was clear. “Parker gave an impression of greyness like the weather ...his eyes and his hair and even his face... were of a neutral grey”. Going further, “the cold grey eyes betrayed not the least flicker of humanity. A farmer would look at a cow with far more interest than this Admiral looked at a Commander”.

Maybe C.S. Forester changed the Christian name to William. In reality, it was Sir Peter Parker who was Admiral at this time. As Admiral of the Fleet, Sir Peter Parker was one of nine admirals present on a barge in Nelson’s water-borne funeral procession on the Thames in January 1806. Among the other admirals with him were St Vincent and Cornwallis.”

The Parker family is also mentioned in Patrick O’Brian’s books again novels based on the facts of the time.

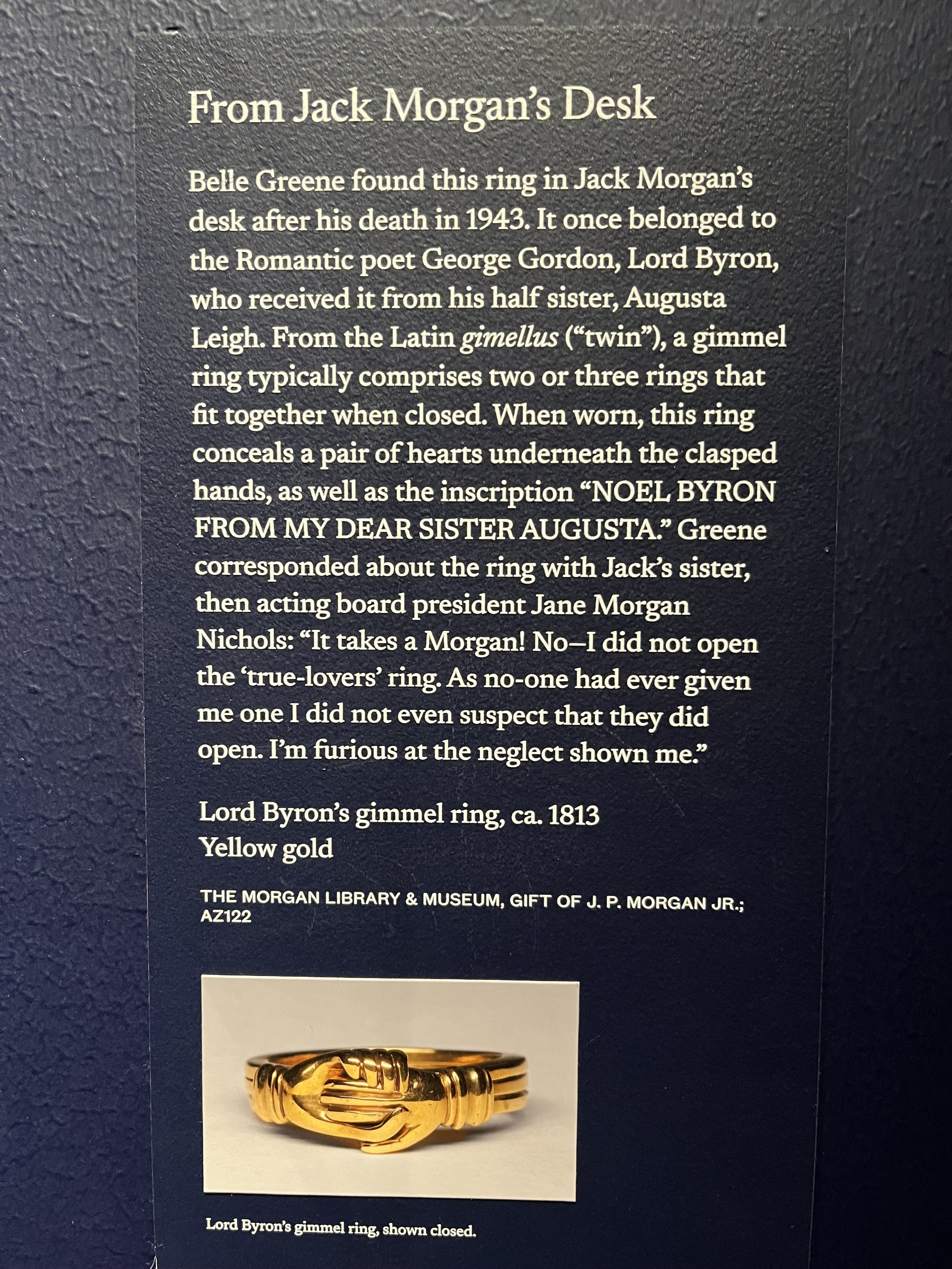

When visiting the Morgan Library in New York, I noticed this ring on display. It was given to Lord Byron by his half sister, Augusta. Augusta Parker was aunt to both of them.

Lord Byron wrote his first ever letter to his aunt, Augusta, November 8th 1798 when he was 10 years 10 months old.